|

Rise

and Fall of RichburgVisions of Wealth and Dreams

Story of

an Oil Boom

From a Sleepy Village It Became as Lively and Wicked

as Mining Camp

When Oil Was Struck

Sixteen Years Ago

Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, Thurs., April 8, 1897

Bolivar (N.Y.) Letter to New York Sun.

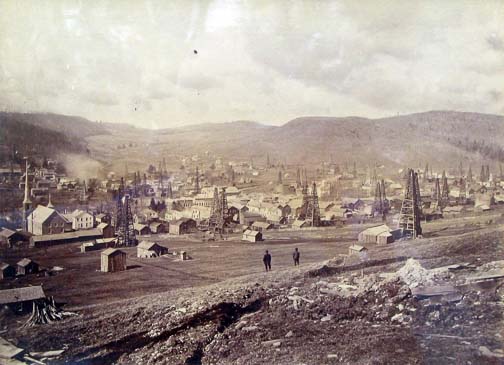

A mile up the valley from Bolivar, in a hollow of the hills of Allegany county,

is the nearest approach to a deserted city to be found in the Empire

state. There are large business blocks with windows boarded up, long

rows of vacant buildings that are tumbling from shaky foundations, a

great brick church slowly crumbling, a brick bank building that cost

several thousand dollars now used as a dwelling house, streets that

are as silent as a churchyard, and over the whole hangs an air desolation

and decay.

Once 8,000 people thronged the streets, and it was as lively and wicked

as any mining camp that ever flourished in the Rockies. All there is to

show of its former greatness are 300 people and the village charter. Three

years ago it was proposed to throw up the charter and a special election

was held. There were not many votes cast, but the majority was on the right

side, and the incorporation papers were not surrendered. It is the one

badge of honor that poor, old, deserted Richburg retains.

Petroleum was responsible for its rise and decay. On April 1, 1881, Richburg

was a country hamlet that did not even boast of a telegraph office. There

were perhaps 25 houses clustered along the shady road that led over the

hills to Friendship, on the Erie Railroad, 11 miles away. The event of

each weekday was the arrival of the stage that carried the mail and an

occasional passenger. On Sunday the villagers went to church and after

that discussed the prospect of an advance in cheese prices if it was summer,

or the price of hay and pine logs on the skids if it was winter. All unmindful

of the fact that billions of feet of natural gas was imprisoned beneath

their farms they hauled beech and birch logs to their dooryards and sawed

them into stove wood every fall, and occasionally one of them grew tired

of trying to get a living from a side hill farm and went West, although

the underside of the farm was lined with a rich oil-bearing sand.

The Pennsylvania oil operators who had followed the line of developments

from Oil Creek to Bradford began to cast their eyes across the state line

toward Allegany County, which was on the "forty-five" degree line. In due

time several test wells were drilled in the county, but none of them gave

much promise of wealth, though several of them produced oil in small quantities.

On the morning of April 27, 1881, a well was completed on the hill above

Richburg that started off at 400 barrels a day. It was known as the Boyle

well, and was the key to a rich field.

Oil scouts who had been watching developments closely, rode with all haste

to the railroad towns over the hills and the wires carried the news of

the big strike to the newspaper offices. The next day people in all parts

of the country knew that a new oil field had been opened. Then began a

wild scramble for leases, and oil operators from the Pennsylvania regions

flocked across the state line in droves, anxious to secure a slice of the

new Eldorado.

Four stage lines were established in less than a week between Eldred,

on the line of the Western New York & Pennsylvania Railroad, midway between

Richburg and Bradford, and the scene of the excitement. The big, old-fashioned

stagecoaches drawn by four horses were loaded with passengers at $3 apiece.

A few days after the strike a building boom struck Richburg. Houses, stores,

saloons and dance halls were built in a night. There was a wild rush for

hotel accommodations. Men willingly paid $1 a night for the privilege of

sleeping on a billiard table, and the regular charge for sleeping in a

bar-room chair was 50 cents. So great was the rush that the hastily built

hotels simply could not accommodate the great crowds that flocked in. It

was nothing strange to see 20 men crawling out of hay mow in the morning,

and many nights during the summer months as many as 200 men slept under

the big maple trees in the little park that surrounded the school house.

A building lot of 20 feet front rented for $50 a month, and choice locations

were scarce at that price.

The men and women who rushed to the new oil field to make their fortunes came from all points of the compass. Pittsburg, Bradford, Oil City, Buffalo, Rochester, and many other cities helped to swell the crowd. The new town was a paradise for crooks of high and low degree. Gambling houses were run wide open, and games of every description flourished. The town boasted of more than 100 saloons, and no attention was paid to securing a license. The people were too busy getting rich to bother about so small a matter. And it was the same way with the gambling houses. One saloon keeper's stock arrived before his building was completed. he had no time to lose, so he put two whisky barrels on end, utilized a plank for a bar, and began business at the side of the street. The first day his receipts were $72. Money flowed like water.

Richburg at that time had two solid banks, a water system, two hose companies,

a fine high school building, a brick church that cost $10,000, a prospective

street railroad, machine shops, oil well supply factories, a nitro-glycerine

factory, and two daily newspapers. The Oil Echo, edited by P.C. Doyle,

now owner of the Oil City Derrick and Bradford Era, was printed on a three-revolution

Hoe press, possessed a news franchise, and was as lively as the town.

About the time the boom burst the Echo office was destroyed by fire, and

Boyle informed the writer that he walked out of town because he did not

have money to buy a ticket. But he is rich now.

As soon as the oil boom was fairly underway, a narrow gauge railroad,

the Allegany Central, was built to Richburg from Friendship and was then

continued down the valley to Olean. The first month a freight car served

as a station and records show the freight receipts amounted to more than

$12,000. In a short time the Bradford, Eldred & Cuba Railroad was built

over the hills from Bradford to Bolivar, and thence across a new extension

of the oil field to Wellsville on the Erie Railroad. A spur was built

from Bolivar to Richburg and a train ran every half hour. It was called

"the dinky line." The engine was a cross between a cookstove

and a fanning mill, but it had a whistle that could wake all the dormant

echoes within

ten miles. Some days this dinky train carried as many as 700 passengers.

The principal part of the criminal business of the county courts came

from Richburg and the outlying oil field. Hold-ups were a nightly occurrence,

and the farmer who came into town with a load of produce had to bring

a hired man with him to guard his load if he expected to realize anything

from it. The most unprovoked murder that ever occurred in the county was

committed on the main street of Richburg in November, 1881, when John

O. McCarthy, a desperado, who had drifted in with the oil boom, stabbed

Patrick Markey, a tool dresser, in front of a saloon. Quick-witted officers

saved McCarthy from being lynched. Horace Bemis, one of the leading criminal

lawyers in the state at that time, defended McCarthy. Judge Charles Daniels

presided at the trial, McCarthy was hanged at Angelica in the following

March. His nerve was good. On the scaffold he asserted his innocence "in

the sight of God," although many of the spectators had seen him commit

the crime.

In Richburg everybody was oil crazy. Wells were drilled in the center of the town on garden lots, and the little village cemetery was surrounded by oil derricks. Even the church people caught the fever, and the trustees decided to invest no more church funds in that kind of gamble. A preacher speculated on the oil market during the week and pointed out the straight and narrow path on Sunday, and no one chided him in the least.

No boom lasts long. In May, 1882, the news of the big gushers down in Pennsylvania, caused a great slump in the oil market, and Richburg's floating population flocked to the new and more promising field. There is nothing more fickle than the floating population of a boom town in the oil country. This was the beginning of the end of Richburg's greatness. Bolivar, a hamlet a mile down the valley, began to boom in the spring of 1882, and soon the Standard Oil Company moved its buying office to Bolivar, and Richburg began to go to seed.

Fires wiped out some of the finest buildings, and others were torn down

and moved to adjacent villages. Buildings that cost thousands of dollars

went for a mere song. The fine opera house was converted into a cheese

factory. The railroads were long ago torn up and a stage line again connects

Richburg with the outside world. The 300 people who live there today are

very loyal to the deserted city and to the village charter. Even the oldest

resident dates everything from the oil excitement. He does not remember

much what happened before that because there was little to remember.

____________

Last issue of The Oil Echo, published for five months in 1882

— dated Wed., July 5, 1882.

Written by the Editor and Publisher, P.C. BoyleNot Dead, But

Sleeping!

_____

THE OIL ECHO

The Representative Journal of the Allegany Field. First Saw Light January

18, 1882.

Struck a streak of bad luck May 19.

— AND —LAY DOWN JULY 5, 1882.

A Case of Suspended Animation

____

After a well-fought battle of five months and eighteen days, in which it by no means got the worst of it, The

Echo, to borrow an expressive but inelegant phrase of the region, "lies down." In its present application the term is merely figurative. It is not a "lay down," in the sense that oil brokers employ the term, but a general vacation in which are included editors, reporters, printers, pressmen and devil. It is a temporary suspension from business, limited only by the continuance of the Warren craze. "When in the course of human events," old Father Time gets in his work on Cherry Grove, and sends the boys back to their old Allegany love, The

Echo expects to be on deck and to greet them open armed, in their dust and travel status by their weary march from the hemlock fastnesses of that awful grove.

Innocent or envious persons not knowing our motives may place a wrong

construction on our action. This step is not a forced one but the result

of calm judgment and deliberate choice. The

Echo for some weeks past has been an open and honest advocate of

a sensible shut down policy in which all ought to take a hand, pointing

out its wisdom and the benefits which would speedily accrue from a general

movement of this kind. And in this connection it is pleasant to reflect

that the oil men were not slow to heed our advice. That they have heeded

it is fully attested in the monthly reports just published. And what,

under the circumstances, would be more natural than for The Echo to

carry into practice a little of its own gospel. It is quite as easy if

not

so convenient for a new paper to stop its presence as for the enterprising

oil man to bridle the drill, and the same as to starting them again.

It affords us no little pleasure to refer to The Echo's proud record.

Other newspaper ventures have had their being in this vale of oil, and

in a majority of instances disaster cut short otherwise long and useful,

if not profitable, careers; but none has fought life's battle more valiantly,

determinedly than The Echo. Its path, never a smooth one, grew more and

more rugged toward the end. Called into life as it was to guard the rights

of the people in this field, its ascent of fame's ladder was rapid and

permanent; every position gained was stubbornly retained to the end. Its

conflict with powerful and grasping monopoly is part of the history of

this field and needs no further reference here.

In the start everything was against us, but the people, and these we

held till allured by superior oleaginous attractions in a distant quarter

they passed beyond our reach. The railroads operating in this field with

a single exception conducted their business with the sole view of getting

people into it without any special references to getting out of it early

in the day.

By this means foreign journals found it easy to compete with us at many

points in our own county. The U.S. Mail was another and very great source

of annoyance to us, inasmuch as it is practically impossible under the

present system to reach, on the day of publication, points almost under

our own nose. But all these things, while they may be peculiar, are by

no means novel. It is possibly the experience of nine out of every ten

candidates for journalistic favor. With the single exception of facility

of circulation, the field was ripe, luscious, when we entered it.

But it's the old, old story of every oil field over again. The hungry prospector invaded a wilderness. The drill went down on 616 and oil came up. Hundreds were attracted to the spot who have not returned. As an example of the shrinkage of business in this field, since May 1st, when 219 wells were drilling; July 1st found but 94. This tremendous shrinkage represents but one branch of the industry, all other branches of it shrank in the same sad ratio, and the crude market more than all.

The 125 wells dropped from the drilling list represents a vast curtailment in labor, and removes nearly, if not quite, $2,000 a day from the currency circulated in an area of less than a dozen square miles. Alarming as were the shrinkages in the departments named, that of commercial values was even greater.

Oil went out of sight, so to speak, and valuable properties went begging.

This field is still in its infancy and its great resources are practically

untouched. When prices appreciate, as some day they must do; the rock

will be called upon to surrender its wealth. When this good time arrives

The Echo will steam up its presses and resume the narration of news events

where it now leaves off.

In conclusion, The Echo desires to return thanks to its advertising

patrons for their patronage. Among The Echo's patrons are to be found

the very

elite of the oil region commerce. It is a source of no little gratification

to us to know that with their patronage we enjoyed their confidence as

well.

____________

Friendship Weekly Register, Oct. 8, 1885

In 1881, at the breaking out of the Allegany oil field, one Jim Parker

struck Richburg with barely a penny about his clothes. A week later found

him worth $10,000. He had bought a good lease and disposed of it, doing

the business with $5.00, which sum he borrowed.

He went through with the $10,000 in a comparatively brief time, however,

and has buffeted "from pillar to post," as the old saying goes. Last week,

however, he made another "raise. " He struck Kinzua a few weeks ago and

by some means procured a lease.

He then let the drilling of a well by contract. It is said that he slept

in the derrick and ate his meals from the driller's pails, till last week

the well was finished and proved a gusher and he sold out, realizing $18,000

clear money. Who will say Jim Parker was not born under a lucky star?

He is well known in Allegany county, having resided at Belmont at one

time.

____________

Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, May

8, 1938

Scio Farmer at 80 Recalls Exciting Richburg Oil Rush

Bolivar - Omer McQueen, who lives a rather uneventful life working his

Scio farm, shut down his tractor, snapped off a "chaw," and recalled a

more exciting day in 1881 when he helped bring in the first Richburg gusher

well which opened the Allegany County oil field.

Almost 80 years old, McQueen is the only member of the history-making

drilling gang alive today. He explained that although the Richburg well

was not the first to be drilled, the few others that preceded it failed

to yield the crude in paying quantities and nobody paid much attention

to them. A backer of one of these earlier ventures, Orville Taylor, was

identified with the Richburg project, which blew in 57 years ago and catapaulted

the Southern Tier into two years of the wildest boom days it has seen.

"It was just this kind of clear spring day, " McQueen reminisced, "and

we had quite a time keeping the curious crowd away from the rig while

the 'shooter' mixed his nitro charge. We all stood tense waiting for the

moment when the torpedo would be sent down the quarter-mile bore, and

we would find out whether we had an oil well or a dry hole."

Recalls Many Delays

He told of nearly two months' work on the "wildcat." Numerous delays,

he recalled, were caused by almost unendurable winter weather part of

the time. "I remember it was on President Garfield's inauguration day,

March 4, 1881, that we finished 'rigging-up," he said. "We had quite a

job moving equipment to our location on top of Richburg Hill. There were

no tractors in those days, and our horses had to make their own pathway

through the ice and snow. To make matters worse, a severe blizzard kept

us shivering in the rig most of the time.

"All in all, we were getting more discouraged every day as the end of

our work seemed farther away with each delay. One of the promoters of

the well offered to sell his share for $100. I told him he would live

to see the day that the land would bring more than that an acre!" This

particular property, now operated by the Birtell estate, is still producing

oil in good quantities, and oil men estimate that the petroleum it has

yielded runs into several hundred thousand dollars."

Strike News Spread

Almost immediately the discovery well roared in, news of the strike reverberated

into the remotest corners of the land. Richburg, until then a hamlet of

a few hundred souls, overnight found itself a roaring boom town of nearly

10,000. It was a matter of only a few days before the landscape was transformed

into a mammoth pincushion of oil derricks, crowded as closely together

as it was possible to erect them. McQueen recalled that while the Richburg

excitement was at its height, Bolivar, a scant mile away, was taking it

all calmly. Its residents were engaged in more staple vocation, lived

in better houses and enjoyed the conveniences of an established community.

Soon the oil fever hit Bolivar as drilling operations moved toward the

south, but not until months later, after the first high pitch had subsided.

Excitement Shortlived

The Richburg excitement was shortlived, he recollected. In May, 1882,

news of gushers brought in at Cherry Grove, Pa., was the signal for a

mad exodus of Richburg's floaters. Here was a bigger and better chance

to get rich, and the fickle oil people flocked to the new Eldorado. In

a few years Richburg had reverted to the sleepy ways of former days, and

Bolivar, which was flourishing under the guidance of more conservative

operators, began to look to their neighboring village as a ghost city.

McQueen related that shortly after the Cherry Hill excitement he quit

the oil business. Weary, he acceded to his wife's wishes for a more peaceful

life and the couple moved to a 30-acre farm near Scio. On the threshold

of his 80th year, McQueen still is energetic enough to do all his own

farm work.

He refuses to take much stock in the predictions of geologists that give

the Allegany field only 10 or 15 more years of existence. "They may be

experts to some people, but they're just plain pessimists to me," was

his comment.

____________

|