|

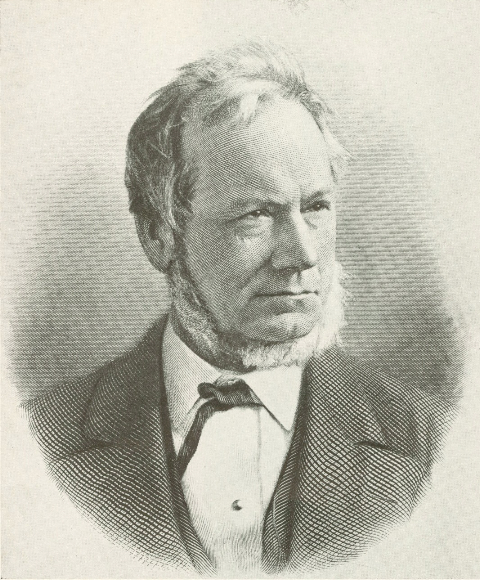

A Biographical Sketch of

Sam Sloan

by

Samuel Sloan (Dec. 25, 1817-Sept. 22, 1907), was a well known 19th century railroad executive. He was a son of William and Elizabeth (Simpson) Sloan of Lisburn, County Down, Ireland. When he was a year old he was brought by his parents to New York. At age 14, the death of his father compelled Samuel to withdraw from the Columbia College Preparatory School, and he found employment at an importing house on Cedar Street in New York, where he remained connected for 25 years, becoming head of the firm.

On April 8, 1844, he was married, in New Brunswick, N.J., to Margaret Elmendorf, and took up his residence in Brooklyn. He was chosen a supervisor of Kings County in 1852, and served as president of the Long Island College Hospital. In 1857, having retired from the importing business, he was elected as a Democrat to the New York State Senate, of which he was a member for two years.

Sloan at 40 was recognized in New York as a successful businessman who had

weathered two major financial panics, but it could hardly have been predicted

that 20 years of modest achievement as a commission merchant would be followed

by more than forty years in constructive and profitable effort in a wholly

different field—that of transportation.

As early as 1855 he had been a director of the Hudson River railroad (not yet part of the New York Central system). Election to the presidency of the road quickly followed, and in the nine years that he guided its destinies (including the Civil War period), the market value of the company’s shares rose from $17 to $140.

Resigning from the Hudson River, he was elected, in 1864, a director, and in 1867, president, of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad, then and long after known as one of the small group of “coal roads” that divided the Pennsylvania anthracite territory. Beginning in the reconstruction and expansion era following the Civil War, Sloan’s administration of thirty-two years covered the period of shipping rebates, “cut-throat” competition, and hostile state legislation, culminating in federal regulation through the Interstate Commerce Commission.

Sloan’s immediate job, as he saw it, was to make the Lackawanna more than a “coal road,” serving a limited region. Extensions north and west, and, finally, entrance into Buffalo, made it a factor in general freight handling. Readjustments had to be made. It was imperative, for example, that the old gauge of six feet be shifted to the standard 4’8 1/2". This feat was finally achieved on May 25, 1876, with a delay of traffic of only 24 hours—in some cases less. The Scranton

Republican of May 31, 1876 noted:

“It is really astonishing in what a brief space of time the herculean task

of changing this great highway has been accomplished, and to the uninitiated

it will seem impossible that so many hundred miles of road could undergo

the necessary alternation in a few hours; yet such is the case.

“What to some would seem a work of weeks, or even months, has been effected in a single day, owing to the thorough and efficient minds that had the matter in charge, and thus is wrought a feat that gives to the D.L.& W. Railroad Company, facilities for sending its trains over every great highway in the United States—the Erie excepted—before the traveling public has time to think of it.”

The total cost of the improvement was $1,250,000. Great changes in the road’s traffic ensued. In the decade 1881-1890, (P.214) while coal shipments increased thirty-two percent, general freight gained 160 per cent, and passenger traffic, 88 per cent. Dividends of seven percent were paid yearly from 1885 to 1905.

The D.L. & W. controlled the Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburg Railroad from 1878

to 1882, which at the time seemed an obvious merger as the railroads connected

at Syracuse, Utica, and at Rome (through its lease of the Rome & Clinton Railroad).

Acquisition of the RW&O was seen as a new market outlet for anthracite coal.

The road’s locomotives were also converted to anthracite coal burners.

By the early 1880s, the D.L. & W. mainline was being extended from Binghamton to Buffalo. It is said Sloan “borrowed” the good steel rails from the R.W.& O, and substituted them with discarded iron rails, so that by 1883, less than 60 of its 417 miles of mainline track were steel rails. The R.W.& O. was allowed to deteriorate by deferred maintenance. It barely escaped receivership. But the road still had great potential. “Look out,” Sloan was once warned, “some one will get that old heap of junk from you yet.” Sloan laughed it off. But eventually he lost control of the road and it went under the new ownership of Charles Parsons of New York, who had carefully had been purchasing R.W. & O. stock at from 10 to 15 cents on the dollar.

Gustavus Myers, in his classic work, “History of the Great American Fortunes” (1909), described Sam Sloan as one of “the monarchs of the land ... the actual rulers of the United States; the men who had the power in the final say of ordering what should be done.”

Sloan was an ally of J. P. Morgan, and one of the founders of what is now Citibank and his name is engraved in stone on the wall in the former Citibank headquarters at 55 Wall Street. There is a statute of Sam Sloan one block from the former Lackawanna Railroad station in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Sam Sloan had little patience with the likes of Jay Gould and Jim Fiske, and the other 19th-century “robber barons.” In his book, “Reminiscences of a Stock Broker,” Edwin Lefere, wrote: “The newspapers never had to beat about the bush with old Sam Sloan.”

Although Sloan resigned the presidency in 1899, he continued for the remaining eight years of his life as chairman of the board of directors. At his death, in 1907, at the age of 90 years, he had been continuously employed in railroad administration for more than half a century and had actually been the president of seventeen corporations. He died in Garrison, N.Y., survived by his wife and six children.

Sam Sloan at the time of his death was director or officer of 33 corporations including Citibank, Farmers Loan and Trust Company, United States Trust Company, Consolidated Gas Company, and Western Union Telegraph Company.

Statue of Sam Sloan at Hoboken. President of the D.L.& W. Railroad 32 years.

During his tenure, trains were not operated on Sunday.

*Note: The subject of this sketch should not be confused with another Samuel

Sloan who was a noted Philadelphia architect. The other Samuel Sloan wrote

a book in 1852 which is still

in print

under

the name Sloan’s Victorian Houses. The book was a best seller when

it first came out. It contained blueprints and designs that

were used

in the construction of many houses.

Sources:

Dictionary of American Biography, PP 213-214, Vol. XVII

Evening Post (N.Y.), and N.Y. Tribune, Sept. 23, 1907

Railroad Gazette, Oct. 11, 1907

J. I. Bogen, The Anthracite Railroads (1927)

Annual reports of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad Company

Information as to certain facts from a son, Benson Bennett Sloan.

|