|

Slaying the Dragon

Bringing an 'Urban Legend' to its Knees

by

P. J. Erbley (Paul Worboys)

Introduction

Did you hear the story of the Lover's Lane murderer with a hook on his

amputated forearm? It was yanked off by a car door handle when his next

victims heard a radio report and peeled out without realizing they were

next—only to find the attached hook the following morning?

How about the ones where the wet poodle was placed in a microwave to

have its fur dried, the exploding toilet, alligators in the sewer, the

vanishing hitchhiker or when the Neiman-Marcus cookie recipe went out

over the Internet?

Great stories all, but merely Urban Legends built on a shred

of truth or just someone's creative imagination. There are websites on

the subject, a phenomenon of three decades or so, inspired by folklore

and plain old legends that may be centuries old.

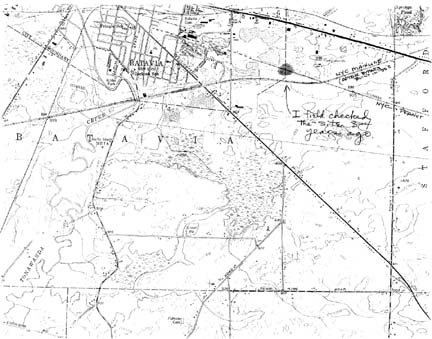

We have our own homegrown legend in these parts, based on a true event

from twelve decades ago, a peculiar piggy-back train wreck in Batavia,

New York, on February 18, 1885. It, or at least the very popular picture

of it, has migrated around the colonies until any upstanding Batavian

should get downright ornery to think other locales have absconded with

it.

The Daily News

Batavia, N. Y.,

Thursday Evening, February 19, 1885

It was a very bad and expensive wreck on the Canandaigua branch of

the Central yesterday morning, and it is a wonder that it was not attended

with loss of life. The stalled train consisting of three locomotives

and two baggage cars met with a little accident itself the night before.

It had the hardest kind of work to get so far along towards Batavia

and had just bunted into a big drift which declined to yield. The train

was then backed up for the purpose of getting a fresh start into the

drift; a pair of trucks under one of the cars went off the track, and

the train could make no further efforts that night to reach Batavia.

There were four passengers on the train—all men—and they

walked to this station, being accompanied by some of the train-men who

came to notify the officials. As the News said yesterday two

locomotives pushed the snow plow down the track to destroy the drifts

yesterday morning, leaving here a few minutes before 8 o'clock.

They rushed down the track at a speed estimated to be at the rate of

forty miles an hour. They knew there were large and hard drifts to contend

against and that it would require great force to overcome them. It is

said now that the rescuers were laboring under the impression that the

train was stalled near the Batavia-Stafford town line; instead of that,

however the train was a full mile nearer Batavia.There were high snow-banks

west of the train, and the snow-plow interfered with the vision of the

rescuing engineers; consequently the snow-plow and the engines that

pushed it went through the drift flying and crashed into the standing

train with great velocity. The shock was so great that the standing

train was forced back the length of a car and a half, and nearly every

wheel was sent off the track.The snow-plow hugged the rails closely,

and slid under the two leading locomotives; the engine part of the first

rode entirely over the snow-plow and struck squarely upon the locomotive

next behind the plow. The tender stopped and rested upon the highest

point of the snow-plow. The second engine ran half way up the snow-plow.

The third engine tried to run under the one ahead of it, but only partially

succeeded. Yet it was a very complete wreck; and the result of a mistake

somewhere. It will take several thousand dollars to repair the damage

that was done.The escape of all parties who were in danger was extremely

fortunate. All the crews were not on the stalled train, some of the

men having walked to this station for breakfast, but when the plow was

seen only a few feet off, some of the engineers were on their machines.

A shout of warning reached every ear and every man jumped, and luckily

saved himself. Engineer Walling was hurrying up the snow-bank when a

flying piece of the snow-plow struck him on the head, cutting a gash,

and engineer Acker was slightly bruised. The men on the locomotives

behind the plow also jumped.

The wrecking force worked hard all day yesterday and for three or four

hours after dark before the track was cleared and put in shape for traffic

today. The locomotive just behind the plow was pulled down with the

locomotive that jumped over the plow riding upon it, though at such

an angle that it seemed as if it would fall over every moment. The snow-plow

with the tender upon it was brought to this station and side-tracked

and later the rest of the wrecked rolling-stock was hauled in. Many

people visited the scene of the wreck during the day.

Conductor McCarthy's train started out at 6 o'clock this morning,

drawn by two locomotives, and Conductor Campbell's train left at 9:30

o'clock.

Conductor Northam's train on the Tonawanda branch staid in the drift

eleven miles west of Batavia all Tuesday night, and yesterday morning,

as no assistance was sent to it, it managed to work its way out and

complete its trip. It came back from Tonawanda last evening about on

schedule time.

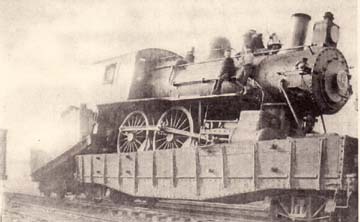

Since every telling is accompanied by the same photograph, the credit

has always been given to Batavia's P. B. Hausenknecht, a photographer

who figured one heavy steam locomotive riding atop another just doesn't

happen every day. Therefore, when you see P.B.'s shot (its copyright protection

long expired), disregard versions that it happened on the Old Colony Railroad

in Massachusetts or on the Erie somewhere in Pennsylvania.

What has happened closer to our realm is that two accidents (35 years

and 37 miles apart) on our late, great little 'Peanut Branch' of the New

York Central Railroad seemed to have glommed into one historical account.

At the time, it was officially the Canandaigua to Niagara Falls branch

of the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad.

During a midwinter blizzard and two miles east of Batavia, a plow train

scooped up a marooned passenger train's locomotive and deposited it on

the engine behind the plow—giving the opportunistic Hausenknecht

a chance to make the wreck world famous—-photographically at least.

In 1920, on the same Peanut line one mile west of Ionia, a plow train

hit an intransigent snowdrift and got piled up quite thoroughly—though

not in the piggy-back style of the former event.

Distilled by time and given to folklore in the retellings, Ionia slowly

emerged as the site of the '85 smash-up. While the 'stolen' event remains

close to the true account, the overlay of it on Ionia's actual 1920 wreck

location seems a most appealing example of a folklorist's craft.

Additionally, this writer heard scuttlebutt floating around the hamlet's

now-defunct "Peanut Line Café" ["Sweet Solutions' is there now] that suggested

one of the locomotives was, to this day, buried near the site of the wreck!

But that is fodder for the second part of this essay, which relates the

true account and the "Urban Legend."

The Beloved Peanut

One month short of 120 years ago, a real calamity hit the Genesee County

metropolis of Batavia. No, not the subject of this yarn per se,

but rather a huge blizzard that roared into the Northeast states and almost

totally shut down this horse, buggy and sleigh age.

Even the railroads, the most reliable way to get from town to town in

such conditions, were mired in snow drifts taller than hay mows. But it

was a badge of honor to railroad men to beat the elements and get their

trains through, especially for the men of the "Peanut Road"—that

downtrodden little "streak o' rust" that hardly had reason to exist in

the first place.

A mere pawn in the game of big time railroadin', the Peanut started out

as the Canandaigua & Niagara Falls Railroad in 1853, a single track, broad

gauge line laid down on old Seneca Indian trails. It rolled through burgs

like Miller's Corners (Ionia today), fostered the suburbanization of staid

old East Bloomfield into tolerating a sister village down in the valley

(Holcomb) and it cut a swath directly through the rough-and-tumble mill

town of Honeoye Falls.

But the fledgling railroad industry was fast becoming a game for the

high-rollers and two roads, the Erie and Corney Vanderbilt's New York

Central, found the C&NF an appealing pawn. Paradoxically, the broad gauge

Erie wanted to buy and double-track it to compete with the Central's mainline

route across the state (Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo), while Vanderbilt

just wanted to block his rival's plan. (Does George Steinbrenner come

to mind here?)

Vanderbilt won the bidding war in 1858, immediately converted the line

to the standard gauge width and went on to generally treat our only link

to the outside world like a wad of gum on the sole of his imported alligator

shoe! To keep the Erie at bay, the coveted right-of-way charter was his

and, legally, he had to keep his trains on it—-just to keep Erie

trains off of it.

The scheme must have worked, since the ever-demeaned Peanut survived

intact until the Holcomb-Caledonia segment via Honeoye Falls was abandoned

in January, 1939. Even today, a bit of it still exists.

As you know, nicknames are hard to shake. 'Shoeless' Joe Jackson played

part of a single game without baseball cleats-poor guy, dead over 50 years

and still 'Shoeless'! Due to its lack of stature, the old Canandaigua

and Niagara Falls was soon and forevermore tagged the "Peanut Line," the

"Peanut Road" or simply the "Peanut." Of course you technical fuddy-duddies

might wish to add that Batavia cut the line in two, so railroad men and

travelers alike referenced the "East Peanut" or the "West Peanut," depending

on which direction the train was heading out of that town.

How the goober moniker came to life is fodder for another story, but,

simply know that it had zip, zero, nada to do with peanuts!

The Unvarnished Truth

On the afternoon of February 17, 1885, and at the height of the aforementioned

storm, Peanut crews damned the conditions and attempted their passenger

runs between Batavia and Canandaigua. After all, wasn't this the line

that withstood the Great Flood of 1865 and, as a result, almost witnessed

Lincoln's funeral train? (Another story, to be sure.)

Conductor McCarthy, whose eastbound train battled heavy drifts all the

way to LeRoy, was surprised to find the westbound of Conductor Campbell

waiting for him beside the depot. Normally, the 'meet' would have been

back at Caledonia, but the going was easier going nose-to-nose with the

blizzard—that is until Campbell's engineer of locomotive #295, William

"Boss" Walling, sensed harsher conditions ahead and decreed his train

would not attempt Batavia that day.

Once McCarthy's train plowed into LeRoy, pulled by engines #296 and #336,

with Samuel Perkins and Ed Wood at the throttles, the crews agreed it

would take a herculean effort to bust through to Batavia. So they hatched

a plan where the eastbound would fulfill its obligation to reach Canandaigua,

then return to LeRoy to assist Walling's train.

All went swimmingly and the two consists were tied together into a juggernaut

of three locomotives and two baggage cars. Not quite certain of their

fate, the railroad boys poured on the coal and rolled into the billowing

white blizzard toward Stafford and Batavia, leaving their passengers to

find hospitality in the warm homes of LeRoy.

Mountains of snow were pushed aside as the train plunged westward. But

fortunes waned as they came within earshot of their goal. First it was

a 'thump'—bigger and more certain than the rest. Then it was a loss

of momentum—crucial in a battle such as this. And finally it was

a blatant 'clunk'—received as the train reversed order in preparation

to rush the snow pack, only to have a set of trucks leave the rails. That

was it, marooned at the Batavia-Stafford town line—or so someone

thought.

A messenger, apparently chosen from the crew for his brawn only, was

sent into Batavia in search of a rescue. Perhaps a more cerebral type

was needed, as the man directed the crew of the rescue train to go to

the township boundary two miles outside the city. Unfortunately, his calibrations

were skewed, as the train lay snowbound at the city limits—not the

town boundary.

So, picture a massive twenty-ton snowplow, pushed through blowing snow

by two monster steam locomotives at a 40 mile-per-hour clip, with visibility

of a few yards, going to a point fully one mile closer than originally

surmised. Do the math—it ain't pretty.

The crew of the stranded train cooled their heels on a snowbank and assumed

their rescuers would toot out a warning in slow approach to the scene.

Little did they know, engineers George Acker and Henry Van Dolan had their

plow train blasting full throttle for them.

(Remember the popular caption under illustrations within every office

cubicle in America? Dripping the connotation of resigned relief, it blurted,

"Thank goodness, it's Friday!" Out in the raging storm of 1885, a botched

reunion was held just east of Batavia—and it wasn't even Friday.)

The resultant 'cornfield meet,' as early railroaders used to call 'em,

created the scene you observe here—and made for a happy ka-ching

in the coffers of one P. B. Hausenknecht, Photographer. Once the obligatory

thunderclap from the collision wafted over the countryside and people

came a-runnin', how many doubted their eyes as the scene came into view.

It is a wonder that the only injuries were sustained by flying debris.

Train wrecks are usually accompanied by engines, tenders and cars strewn

for hundreds of feet in all directions, then eventually cleaned up and

generally forgotten. This event was unique. While virtually no piece of

rolling stock left the rails laterally, Walling's engine #295 was scooped

up and pitched over the snowplow onto Acker's trailing #470, Perkins'

#296 was caught climbing the face of the plow, with Wood's #336 commencing

the same antic.

Engineer Acker was ever-diligent for trouble and a good thing too. for

he'd a been a goner otherwise. Spotting the snowbound train fast looming

up out of the sea of white, Acker hit the brakes, yanked the whistle cord

and shouted a lung-full of "JUMP!!" to his fireman. Those back in Van

Dolan's #362 took the hint and followed suit. They "joined the birds"

just before impact and, rolling in the snow, they missed #295's flight

and subsequent crash-landing that completely squashed Acker's cab. Upon

viewing the result, little did anyone know this slice of rural America

would be immortalized in picture and print for decades to come.

In an era when many railroad viaducts were still of the covered type

shown on Honeoye Falls postcards (replaced in 1893 with a steel plate

girder bridge), the wrecking crews found the location to their liking.

The piggy-backed #470, which never left the rails, was simply pulled into

Batavia with intact #295 riding along pretty-as-you-please—albeit

with a rearranged face.

For several days, and while a removal plan was created, the conjoined

locomotives sat on a switch near Swan Street and served as a tourist attraction.

As there were still bridge obstacles west of Batavia, there was no going

to Buffalo, where a heavy wrecking crane could do the work. It was decided

instead to dig a pit (keep this concept in mind when the Ionia crash is

described), pull the mess into said pit until #295 was at ground level

and #470 was 'buried' below, then place rails to #295 and pull it to freedom.

Once removed from its back, #470 was drawn from its hole and the two

were sent to the repair shops and subsequently returned to service.

If not for it being the dead of winter, some two-bit capitalist might

have set up a booth and charged admission to witness the whole gritty

industrial pageant. At least the memory lingered for a long, long time.

Photographer Hausenknecht saw to that!

Batavia Postscript

For years thereafter, the piggy-back wreck was the exclusive domain of

Batavia, NY (which loved the notoriety) and the New York Central & Hudson

River Railroad (which, of course, hated such fame).

Periodically, the Hausenknecht print, with all due credit and description,

would be found in a newspaper or magazine. Around the 50th anniversary,

various companies used it in calendars and Ripley's Believe-It-Or-Not

even added to the exposure.

Even the city of Batavia got involved by producing a screen-printed shirt

of a drawing of the piggy-back wreck. Thanks to a request in the 'Who-Knows'

column in the Pennysaver and a response from an elderly railroad

man from Batavia, this writer has his own Bicentennial commemoration of

that famous day. (If he were anywhere near his playing weight, he'd show

it off around town. But in the here-and-now? Forget it.)

Then it started to get ugly. Sinister forces went to work, as time blurred

memory and detail—followed by the demise of the principals of the

story. Combined with actual, but very rare piggy-back train wrecks, the

Hausenknecht picture endured, as local writers fudged the details and

made Engineer Acker's poor old #470 the universal victim.

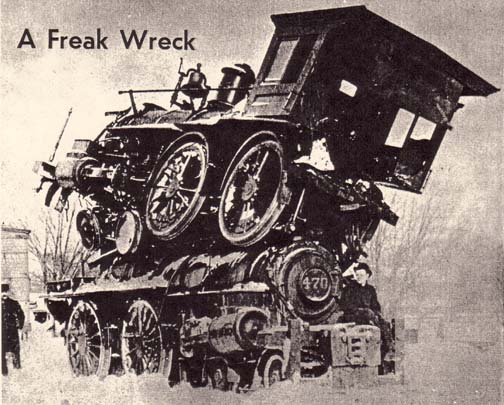

For instance, a national magazine related a similar event on the Old

Colony Railroad, near Marlboro Junction, Massachusetts. Entitled "A Freak

Wreck," the pick-a-back actually happened, but the photo was pirated and

#470 was the foil once again. Apparently, in lieu of an authentic photo

of that collision, the author 'adjusted' the details to fit the Batavia

portrait.

Photograph of the wreck on the Old Colony Railroad near

Marlboro Junction, Massachusetts, February 3, 1898

A noted local historian and folklorist wrote a wonderful story about

the Batavia occurrence. "An Unexpected Scoop," gave a mostly accurate

presentation of the details and the characters involved—except for

the pileup getting transferred 37 miles to the east. A few months later,

this author's story was adapted by a regional magazine, "Stranded by a

Genesee Country Winter," with at least one major adjustment in the story

line.

Rather than having the locomotive pairing towed to Batavia, someone realized

the presence of covered bridges along the Peanut prevented such a maneuver.

The editorial switcheroo read in part, "They could not be towed to the

Batavia railroad yard because they would not fit under bridges. Workers

finally dragged the whole mess into a sand pit...when the ground thawed,

teams of horses dug a huge hole and buried the bottom engine [#470] until

Walling's engine #295 was level with the ground. Then, they dragged it

off the top with teams of horses and mules."

What was created among our local populace, was a classic Urban Legend,

where the elements of truth were diluted in a dose of fiction and good

storytelling. The key change was in the location, which exited Batavia

and found a home in the woods outside Ionia.

Additionally, like hidden treasure, a steam engine sits buried in a sand

pit near the long-abandoned right-of-way? People have looked for it, metal

detectors have detected it, but no one has proven that it is there. It

is a dubious assertion, to be sure.

The Wreck of 1920

Ionia certainly had its share of railroad history, as the New York Central's

Peanut was the life-blood of the hops, produce and field crop industries.

Wagons brimming with beer hops streamed out of the Bristol Hills and local

farmers hauled many a harvest through town to be sent by rail to far-off

markets. Heck, "Asparagus Junction," a crafts shop in the old Ionia depot,

wasn't named out of thin air—there was the region's agrarian heritage

to honor.

In 1920, for instance, the year commenced with one blanket of snow piled

atop another. By February, lingering piles of cleared and drifted snow

left the roads and rails but mere channels for passing travelers. There

was little room for error, especially when it came to the railroads.

On Tuesday afternoon, February 10th, Honeoye Falls' country doctor, H.R.

Marlatte, and his driver had just begun their return trip from an Ionia

house call. Reaching the hamlet's four corners crossing, where the Peanut

followed a diagonal route through the intersection, wind-driven snow obscured

the doctor's cutter from the sight and sound of the westbound 4:35 passenger

train.

Before they knew it, the locomotive leveled a glancing blow to the conveyance,

killed and carried off the horse and sent the riders flying into a convenient

snowdrift. Badly shaken, but otherwise intact, the bruised men arrived

home to contemplate their good fortune as the buzz around Ionia spread

from household to household.

Just one week and many inches of snow later, a greater hubbub swept through

the area and by Saturday, February 14th, after Marlatte's set-to, recurring

storms served to block Peanut rail traffic. The Central brass decided

to 'get rough' with nature's antics and, on Tuesday the 17th, a hefty

plow train, under the guidance of engineer Samuel Gersley and comprised

of a one-sider plow, two locomotives, two cabooses and a flanger car,

headed west out of Canandaigua

On it came, through Wheeler's Station, Holcomb and Ionia, blasting snowdrifts

with aplomb. The crew of five must have thought such a run was mere child's

play and the route to Batavia would be open in short order. That is until,

a mile beyond Ionia, a meek-looking drift turned out to be solid ice.

The train left the rails, jack-knifed until its units were akimbo and

the five-man crew painfully injured. One engine was on its side and facing

the direction from which it came and the other was in a tipsy pose well

off the rails. The plow, which was ill-suited to a single track line,

was found more or less destroyed, with its thoroughly crumpled nose lifted

to the North Star.

Rochester Democrat & Chronicle

February 19, 1920

Canandaigua, Feb. 17—A huge snowplow and two locomtives came

to grief this forenoon at mile post No. 14, a mile west of Ionia station

on the "Peanut" branch of the New York Central Railroad, while

engaged in an effort to clear the branch of the snowdrifts that have

held it bound tight since Saturday evening, when the last train ran

over the road between this city and Batavia. Five men were injured in

the wreck, three of them seriously. The rolling stock was badly smashed,

the plow being practically a compete wreck. One of the engines lies

on its side in the ditch alongside the track headed towards the direction

from which it came, and the other is also in the ditch, but did not

turn completely around. The plow is standing with its nose up a high

bank, where it was shoved by the force of the two locomotives behind

it.

Fortunately, a passenger train, following an hour behind, came upon the

scene, received the injured and hurriedly backtracked to Canandaigua's

hospital. A wreck train was ordered to the site of the mishap and strong-backed

farmers were hired to chop and dig out the line.

Wrecking cranes, equipment and crews of 1920 were far more capable of

clearing a crash site than in 1885, when a buried and abandoned locomotive

was only slightly more plausible. For arguments sake, even if a piggy-back

situation existed, no railroad would leave one of its 'own' behind—the

collective ego would not allow it.

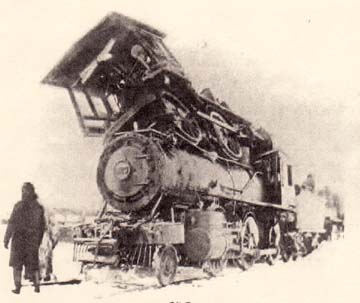

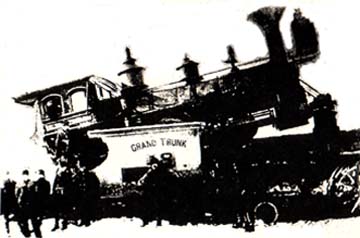

Photographs of other piggy-back train wrecks.

At a time when NYC bigwigs may have already been considering the Peanut's

scrap value, there was little doubt any wrecks would be summarily cleaned

up. By 1925, crystal ball showed that automobiles and trucks were winning

America. Economical two-unit, gasoline-powered 'doodlebugs' carried a

few loyal passengers and there was so little freight that, by 1939, Ionia's

tracks disappeared from the landscape altogether.

It Lives!

Here, in the new millennium, there are people out Ionia way who will

tell you the standard mantra of the story. It all sounds very convincing,

especially when told by one fellow, "I know where it happened, my metal

detector registered 'Big Iron' and it has a forty-foot outline." Hmmmm.

Hopefully this spring we will keep a date to do a little digging out

in the hinterlands of West Bloomfield town. One of us will be made a fool,

have egg on our grizzled mug or break out in hives. The dragon will be

dealt with one way or the other.

But what if it's not found, does that mean it's not out there somewhere?

This writer tells people of a pithy headline from a 1913 newspaper, "Shortsville

Man Leaves Toes in Canandaigua." No one believes me, until they see the

clipping about the careless fellow's failed attempt to board a moving

freight train.

A legend, once hatched and incubated over a generation or more, will

never cease its work. Even tonight, some couple out on Lover's Lane will

sense a hook moving stealthily toward their car door. Personally (ahh,

the smell of homemade Neiman-Marcus cookies baking in the oven), the hook

murderer and buried locomotive tales, are, until proven otherwise, balderdash!

Illustrations provided by the author.

|