|

The "Alien Proprietership"

The Pulteney Estate during

the Nineteenth Century

by

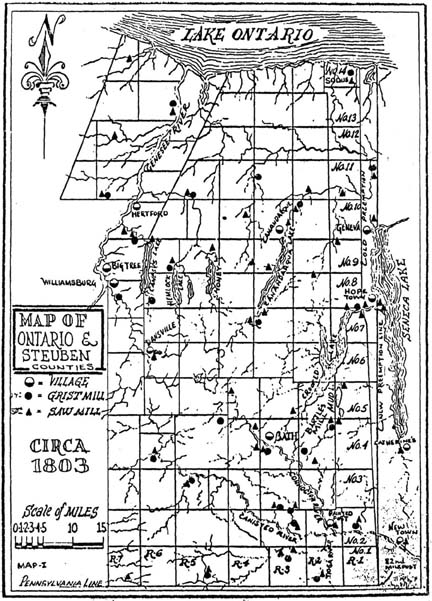

For most of the nineteenth century much of the land in Steuben County

was owned by subjects of the British crown. Sir William Pulteney, John

Hornby, and Patrick Colquhoun, or their heirs employed local agents to

manage and sell their property. The land office on the south side of Pulteney

Square was a local landmark. This foreign ownership had a significant

and sometimes negative impact on the economics and politics of the county.

Yet the story of the "Pulteney Estate," as it was usually called, has

not been fully told either in local or general histories. The activities

of the first land agent, Charles Williamson, a Scottish immigrant, are

well known, but he was employed by Pulteney and his associates for just

a decade, from 1791 to 1801. For three-quarters of a century thereafter

the Pulteney land office in Bath continued to be a center of economic

power, an object of both public respect and resentment, and sometimes

a target of political retaliation.

Pulteney and Hornby were wealthy men who looked to increase their wealth

still further by investing in American lands. In 1791 Robert Morris, a

prominent Philadelphia financier, was looking for a quick sale of the

one million acres of Genesee lands he had purchased the previous year

from Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham. Morris needed the money to try

to pay off his extensive debts. He sent William Temple Franklin (a grandson

of Benjamin Franklin) to England to look for buyers. Patrick Colquhoun

was impressed with the promotional pamphlets and the engraved map which

Morris had published. Colquhoun told John Hornby and Sir William Pulteney

about the investment opportunity. On their behalf Colquhoun negotiated

a purchase from Morris: one million acres of Genesee lands for roughly

$275,000. The partners agreed that 9/12 of the property should belong

to Pulteney, 2/12 to Hornby, and 1/12 to Colquhoun for his role in negotiating

the transaction. The one legal obstacle to the deal was a New York statute

barring aliens from owning real estate. This law was circumvented by instructing

Charles Williamson, who was picked to be the agent in America, to become

a United States citizen so that he could hold legal title to the Genesee

lands.

CHARLES WILLIAMSON

1757 - 1808

David Robertson Williamson commissioned this copy of the original

portrait of his grandfather in 1893 and presented it to the Village of

Bath on the occasion of its centennial. This portrait is displayed in

the Magee House in Bath and is reproduced here by courtesy of the Steuben

County Historical Society.

When Williamson arrived in America and inspected the purchase in the

spring of 1792, he discovered that it consisted of the less valuable agricultural

lands in the Phelps and Gorham Purchase—the hilly country of the

south and the sometimes marshy or sandy lands near Lake Ontario. The townships

in the fertile plain between Canandaigua and Geneseo had already been

sold off, likewise several townships containing valley flats in future

Steuben County. But the Pulteney purchase did embrace the promising sites

of Geneva, Sodus Bay, the falls of the Genesee where Rochester now stands,

and the junction of the Genesee River and Canaseraga Creek, south of Geneseo.

At each of these places Williamson or his associates laid out towns. Williamsburgh

on the Genesee soon disappeared, but the other settlements have become

modern cities or villages. The capital city of the purchase was to be

Bath on the Conhocton, founded in 1793 and named for the English resort

town which was Sir William's favorite residence.

Charles Williamson recognized that the isolation of the Genesee country

discouraged settlement and hindered transport of produce to seaboard markets.

He perceived that the Susquehanna River and Baltimore were the natural

trade route and port for the Genesee country. One of Williamson's first

acts was to order a road to be opened from the West Branch of the Susquehanna

to the Genesee. It was built in 1792-93 with the labor of German immigrants

recruited by one Wilhelm Berczy, who was hired by Patrick Colquhoun. Williamson

also invested in the great road running westward from the Mohawk River

to Canandaigua, and in a few local roads. He constructed a large stone

hotel at Geneva and a frame tavern at Painted Post, held fairs and races

at Williamsburgh and Bath, and sponsored newspapers at Bath and Geneva.

He lobbied successfully for a post route over the new road to the Genesee.

As a member of the state Assembly in Albany, he sponsored a bill erecting

a new county, to be named Steuben, in 1796. And Williamson hired surveyors

to subdivide his lands, sub-agents to make sales, and bookkeepers to account

for the money received and expended.

All these projects cost a great deal of money, which Sir William Pulteney

supplied, patiently at first, then with growing concern. Williamson's

expenditures in his ten years as agent totalled $1,374,470, while his

receipts from land sales amounted to only $147,975 plus a much larger

amount due on mortgages. Most of the land sales were made to speculators

who soon defaulted on their mortgage payments. Actual settlers were slow

to come. In 1800 Sir William and his associates decided to replace Williamson

as agent. His successor was Robert Troup, a stout, cautious Federalist

lawyer of New York City. Troup had invested in Steuben townships in the

mid-1790s and was familiar with Williamson's business practices. With

the change in land agents, Williamson was required to convey his lands

to the British investors. The conveyances were executed by deeds dated

in December 1800 and March 1801.(A statute passed in 1798, at the urging

of Williamson and others, permitted conveyances of real property to aliens

for three years only, and the deadline was near.) In a complex settlement,

the lands conveyed to Pulteney, Hornby, and Colquhoun were allotted among

them proportional to their original investments (9/12, 2/12, 1/12). They

agreed to pay Williamson the salary that was due him, to assume his enormous

debts (not paid off until 1818), and to release him from any future legal

claims.

The lands which Williamson deeded in 1800-1801 comprised about 1,335,000

acres. The principal lands were those which he had purchased from Robert

Morris in 1792, excepting the few lots subsequently sold. Williamson had

also acquired several other large tracts of land. One was the narrow eighty-mile

triangular tract, or "gore," between the old and new preemption lines.

The preemption line ran from the Pennsylvania line north to Lake Ontario,

in the vicinity of Seneca Lake. (The old preemption line, run in 1788,

deviated significantly from true north-south; the new line corrected the

error. Lands west of the preemption line had been claimed by Massachusetts

under its colonial charter. By a 1786 agreement, the lands became part

of New York, but Massachusetts retained the right to sell them, and conveyed

them in 1788 to Phelps and Gorham.) In 1795 Williamson obtained a patent

for most or all of the present towns of Huron, Rose, Wolcott, and Butler

in eastern Wayne County. The State of New York granted this patent in

return for Williamson's recognizing the claim of Seth Reed and Peter Ryckman

to a tract of land in the gore between the two preemption lines, north

of Geneva. Williamson also bought lots in the township of Galen, which

lay within the Military Tract designated for grants of land to Continental

officers and soldiers. He acquired the "North Little Gore" along the shore

of Seneca Lake, east of the old preemption line in present-day Yates County.

In the eastern and northern parts of the state, Williamson purchased the

Otego Patent in Otsego County; about 10,000 acres of township no. 8 in

Franklin County; portions of the patents of Nobleborough, Jerseyfield,

and Jessup's Purchase in Herkimer County; most of the towns of Eaton,

Madison, and Lebanon in Madison County, which lay within the Chenango

Twenty Townships; and a few lots in Albany and New York City.

To the west of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase, Williamson acquired several

large tracts in the Morris Reserve, which lay between the Genesee River

and the vast holdings of the Holland Land Company, the popular name for

a consortium of Amsterdam businessmen. The Pulteney associates held a

$100,000 mortgage given by Robert Morris on the Morris Reserve. When Morris

failed to make payments on the mortgage, he conveyed 50,000 acres in the

Cottringer Tract to Williamson to satisfy the obligation. This tract straddled

the Genesee River in present-day Allegany, Livingston, and Wyoming Counties.

Another Williamson acquisition in the Morris Reserve was an undivided

half share in the 100,000 Acre Tract in present-day Orleans and Genesee

Counties, conveyed to him in 1801. Williamson also bought a few thousand

acres in Pennsylvania and present-day West Virginia.

The deeds of 1800-1801 gave rise to two legally distinct land agencies:

one for the real estate of Sir William Pulteney and another for the real

estates of William Hornby and Patrick Colquhoun, the lesser partners in

the original association. John Grieg of Canandaigua, like Williamson an

immigrant Scot, served as general agent of the Hornby-Colquhoun interests

from 1806 until he retired from the post in 1852. At that time William

Jeffrey, his assistant, took over the agency and finally bought the few

remaining Hornby lots in 1875. At the beginning of the nineteenth century

the Hornby and Colquhoun properties had comprised some 300,000 acres,

about a third concentrated in Steuben and eastern Allegany Counties, another

third in the Chenango Triangle in Broome and Chenango Counties, and the

rest in other locales. Dugald Cameron and after him William W. McCay served

as sub-agents for the Hornby Estate in Steuben and Allegany Counties.

Charles Cameron, brother of Dugald, served in the same capacity for the

Hornby lands in the Chenango Triangle. John Grieg purchased the unsold

Pulteney lands in the Cottringer Tract and elsewhere in Genesee County

in 1817, and he bought out the Colquhoun interest in 1837. But the Pulteney

family continued to own extensive lands, mostly in Steuben and Allegany

Counties, for several decades to come.

At the opening of the nineteenth century, after the abrupt departure

of Charles Williamson, Sir William Pulteney's new land agent Robert Troup

found Williamson's business affairs in disarray. While the account books

and filed papers at the Geneva land office were in quite good order, those

at the Bath office were a disordered mess. Many townships remained partly

or wholly unsurveyed, and no orderly land sales were possible without

good surveys. Bath was a few dozen log and plank houses huddled around

Pulteney Square, itself a jumble of stumps and grass where cattle grazed.

The whole of Steuben County contained only 1,788 inhabitants in 1800.

After his first inspection tour in 1803, the new land agent, Robert Troup,

described them as "poor, uninformed, and of less respectability than the

settlers of any of the new counties through which I have passed." Troup

reduced expenditures and reorganized the land office staff. He listened

attentively to the settlers' pleas that he sell lands with no down payment.

But after Williamson's disastrous experience with land sales to speculators,

Sir William Pulteney was now insisting that each settler make a down payment

of one fourth of the purchase price in cash. In 1804 Troup gave up trying

to obtain money the settlers did not possess. Without his employer's permission,

he ordered the sub-agents at Bath and Geneva to sell land on credit. However,

each purchaser was required to settle on the land and make improvements

within a specified time period, usually six to twelve months. When a lot

was sold, title to it was not yet conveyed. The Pulteney land office sold

land by contract, which in legal terms gave the settler the possession

but not the fee (ownership). The settler was responsible for paying the

taxes but did not receive a deed until the purchase price and accumulated

interest were completely paid off. The land office preferred using the

land contract instead of the mortgage, because the contract could be declared

null upon any failure to fulfill its terms. Mortgage foreclosure was a

lengthy, costly legal proceeding in the Court of Chancery.

Robert Troup hoped that transportation improvements would help bring

prosperity to Steuben County. He invested heavily in the turnpike companies

that were promising to build better roads westward across the Southern

Tier counties. The Lake Erie Turnpike Road, completed between Bath and

Angelica by 1810, was funded almost entirely by the Pulteney land office

and by Philip Church of Angelica. Other road improvements were intended

to channel traffic in produce southward to the rivers feeding into the

Susquehanna. For example, in 1807 George McClure, a merchant and miller

of Bath, opened a store at Pittstown (now Honeoye), Ontario County, and

cut a road from there "to the head of the Conhocton River." McClure informed

Troup of this improvement, and Troup authorized Samuel S. Haight, the

sub-agent at Bath, to subscribe $350 for improving the highway from the

"head of the Conhocton" to Bath. As much of the cost as possible was to

be paid by the labor of settlers indebted to the Pulteney Estate. Robert

Troup hoped that these investments would be "further proof of my sincere

desire to benefit the county; notwithstanding what particular individuals

in the county may say to the contrary." In 1808 another road was completed

from Bath southwest to the Canisteo River, then south through the new

town of Troupsburgh to the 109th milestone on the Pennsylvania line.

Robert Troup

1757 - 1832

Born in Hanover, Morris County, New Jersey. Graduated Columbia,

1774; studied law under John Jay; friend of Alexander Hamilton; was in

Revolutionary War; member of NYS Assembly; Clerk of U.S. District Court;

Judge of U.S. District Court, 1796-98; private practice; Pulteney agent,

1801-1832. Portrait by permission of Columbia University Archives —

Columbiana Library.

Settlers hoped to raise wheat, the most lucrative cash crop. Wheat

brought a high price in the early years of the nineteenth century because

of high demand in Europe during the Napoleonic wars. Wheat prices at

Bath were considerably higher than at Canandaigua or Geneva because

of the successful ark navigation to Baltimore via the Susquehanna River

and its tributaries. The high wheat prices, better terms for land sales,

and improved access to markets began to attract settlers to the Pulteney

lands. However, the few good years were followed by many bad ones. Hard

times began in 1808, when President Jefferson imposed a temporary embargo

on all foreign exports because of British harassment of American shipping

on the high seas. In Steuben County the economic distress continued

with little relief through the war with Britain, the post-war depression,

and the prosperity that came to other parts of New York State with the

opening of the Erie Canal in 1825.

The Pulteney land agents were obliged to pay off Williamson's huge

debts and to send remittances to the Pulteney family in England. In

order to force the settlers to pay something, the land office began

about 1813 to charge compound interest on most land contracts. That

meant that unpaid interest was added to the principal, and interest

then was charged on the whole. In countless cases the settler accumulated

a debt so large that he lost his farm and all the improvements he had

made—house, barns, cleared fields and pastures. In the expressive

language of the settlers on the Pulteney Estate, he "starved out." Some

lots were said to have been sold as many as eight or ten times, and

each time the land agent and sub-agent collected a commission on the

sale. Settlers complained bitterly that this system encouraged the land

office to evict settlers from their lands and sell again to others.

This happened sometimes, but the agents were usually lenient with settlers

who managed to pay something. Troup and his employees pointed out that

they had spent many thousands of dollars on turnpikes, roads, and charitable

purposes. But the settlers could not forget that their hard-earned money

went to further enrich already wealthy Englishmen.

For several years after Sir William Pulteney's death in 1805, Robert

Troup's biggest headache was his relations with the Pulteney heirs,

who were either uninterested in agency affairs or else tried to interfere.

The heirs also died in rapid succession, resulting in repeated uncertainties

about the legal title to the Pulteney estate and Troup's power to administer

it. Lady Bath, Sir William's daughter, died in 1808. she left her real

estate to her cousin, Sir John Lowther Johnstone, and her personal estate

(including bonds, mortgages, and contracts for land sales) to her husband

Sir James Pulteney and to trustees for other relatives. This division

of Sir William Pulteney's estate was the origin of the legal distinction

between the Johnstone Estate (lands unsold at the time of Sir William's

death) and the Pulteney Estate (lands sold conditionally at that date)

in the account books kept by the land office clerks. All the property,

however, continued to be known popularly as the "Pulteney Estate." Sir

John and Sir James both died in 1811. The Johnstone (real) estate was

placed under the management of a succession of trustees who administered

it for the Johnstone heirs. The Pulteney (personal) estate passed down

to various genteel members of the Pulteney family. For many years both

branches of the Pulteney-Johnstone clan were generally content with

their remittances from America, and they took little interest in the

details of agency management.

A Bath lawyer, William Howell, observed that "about the stiff rooms

of the land office there was a seclusive chilliness that spoke of English

aristocracy." The agents and employees included both Englishmen and

Scotsmen. Williamson was a Scot; Dugald Cameron, another Scot, was sub-agent

in Bath for many years. Joseph Fellows, born in England, was sub-agent

at the Geneva land office; he became principal land agent after Robert

Troup died in 1832. Several other land office employees were also immigrants

from Great Britain. Their accents and manners gave the agency a character

that inevitably clashed with the growing democratic ideals of the new

United States. Some of the agents got along better with the settlers

than others did. Neither the stout, cautious, American-born Troup nor

the parsimonious bachelor Fellows was beloved by the settlers. Anyway,

they lived far away. Troup resided in New York City, Albany, or Geneva,

and visited Steuben County once a year. Fellows lived in Geneva until

1856, when he moved to Bath. Williamson was well remembered and regarded

for his many generous acts. His financial blunders, the cost of which

was passed on to the settlers, were seemingly overlooked. Dugald Cameron

lived in Bath and was generally liked, with good reason. In the early

1820s the list of defaulting debtors grew to "frightful" length, in

the opinion of Robert Troup. Yet Cameron was slow and reluctant to obey

Troup's orders to evict the delinquent settlers. Cameron was elected

to the state Assembly in 1828 and died while in Albany. Over two thousand

people attended his funeral in Bath.

Though some land office employees were liked as individuals, the settlers'

usual attitude toward the Pulteney Estate was one of hostility tempered

by dependence. Settlers chose indirect, silent ways of expressing their

dislike for the land office. Grain given as payment on land contracts

often was smutty. Published notices insisted again and again that the

wheat, corn, and rye brought to the land office "must be clean and merchantable."

Theft of timber was continual. The standard land contract forbade the

purchaser from "destroying any timber growing on said Land, over and

above what may be necessary and proper for fuel and buildings, fences

or other improvements." This provision was impossible to enforce. A

report on Pulteney lands in the town of Italy, Yates County, in 1828,

declared that fine timber stands had been the "object of reckless waste

and wanton depredation. The best part of the pine is gone and the proprietors

[the land office] have received little or nothing for it." It was no

different in other towns. In 1846 the Pulteney Estate brought several

lawsuits against settlers who had stolen substantial amounts of timber.

For example, one Cohocton man was charged with taking $500 worth of

pine, hemlock, maple, cherry, beech, and basswood trees. The jury found

him guilty, but awarded the plaintiff only four dollars in damages.

The jury's sympathies apparently lay with the defendant, not with the

land office. A survey of Pulteney lands in Steuben and eastern Allegany

Counties, made in 1861, found that many of the lots still under contract

for sale were "pretty well stripped" of their valuable timber by previous

contractors who had never gotten deeds.

The basic problem was a burden of debt too great for the settlers to

bear. The price of wild lands in Steuben County was usually $2 or $3

per acre. This price might have been bearable if the price of wheat

had stayed at $1 a bushel, as it was before the War of 1812. Instead

the price fell to 75 cents by the mid-1820s, and 62½ cents in 1830.

Facing the same problem of falling produce prices, in the later 1820s

the settlers on the Holland Purchase west of the Genesee River successfully

petitioned for lower land prices. Settlers on the Pulteney Estate took

note of this and decided to act. In January 1830 a convention of settlers

of Steuben and Allegany Counties was held in the Presbyterian meeting

house in Bath to consider common grievances against the Pulteney Estate.

Each town sent delegates. Chairing the convention was Henry A. Townsend,

a Bath resident who had immigrated from England and once served as county

clerk and surrogate. The convention's memorial to land agent Robert

Troup recounted the events that had left the local economy in a state

of what it termed "stagnation": the sharp drop in agricultural prices

after the War of 1812; the shift of commerce and immigration to the

Erie Canal, completed in 1825; and the reduction of the price of lands

on the Holland Purchase and of federal lands in the western states—the

latter to a price of only $1.25 an acre. The settlers' principal demand

was that the price of lands in Steuben and Allegany Counties be lowered

to a level they could afford to pay.

Robert Troup's reply was issued in March 1830 by William W. McCay,

the sub-agent at Bath. To the settler's surprise, Troup agreed that

the debts owed by them were "generally too large for their means of

payment." He proposed an independent appraisal of the settlers' lands

and improvements to establish a fair price for renegotiated contracts.

The appraiser should be an "independent, judicious, and upright farmer,"

acceptable to both sides. Settlers who entered into a new land contract

would have to pay some money down. Troup would continue the practice

of accepting wheat and cattle in payment of debts; wheat would be taken

at 75 cents per bushel, higher than the current local price. And he

had already directed the sub-agents to reduce the price charged for

unsold lands.

[to be added shortly]

This isometric drawing shows the recollected shapes

and locations of buildings in the Village of Bath in 1804. The Pulteney

Land Agent’s Residence is number 14; the Land Office is number

15. Could (editor’s question) number 13, The Log House, be the

“log building on the south side of Pulteney Square, of sufficient

capacity for the accommodation of Captain Williamson’s family

and the transaction of his official business”? (From bottom of

page 112 of Ansel McCall’s “Historical Address” in

The Centennial of Bath, New York 1793 - 1893. Also described at the

top of page 116 as the “Temporary abode of Captain Williamson,

which answered the purpose of parlor, dining-room and land office.”)

The settlers' delegates met again and rejected these seemingly generous

proposals. They recommended that all settlers indebted to the Pulteney

Estate withhold payments until satisfactory relief was granted. At further

meetings in various towns, resolutions were passed demanding a reduction

of all debts to the current value of wild lands. Troup vehemently rejected

this demand. He argued that it would be unfair to those settlers who

had made payments on their contracts, favor those who had paid nothing,

and besides result in a loss for the Pulteney Estate. He stood by his

plan for an appraisal, and he noted that many settlers had already come

in to the land office in Bath and negotiated new contracts at lower

prices. He threatened legal action against those who continued to withhold

payment. Troup concluded his long "manifesto" by urging McCay to treat

the settlers with "courtesy and kindness." But he made clear his conservative

devotion to the "the rights of property—rights which constitute

the main pillar that supports the fabric of our free and excellent government."

There was no organized response to Troup's manifesto over the summer

of 1830, probably because settlers were busy with farm work. In October

the corresponding committee summoned the convention delegates to meet

again at Bath. This meeting saw the effective end of the settlers' protest

movement, because the proceedings became embroiled in partisan politics.

Grattan H. Wheeler, the farmer whom Troup had chosen to appraise the

settlers' lands, had recently been nominated to run for Congress. His

opponent was John Magee of Bath. Wheeler had the support of the Anti-Masons,

the friends of Henry Clay, some Democrats, and his own relatives and

neighbors. Magee was backed by the "old democratic party under the control

of what is termed the Albany Regency, who are all Jacksonians" (meaning

the party of ex-Governor Martin Van Buren and President Andrew Jackson).

At the convention on October 19 Magee's supporters accused Wheeler and

his supporters of calling the meeting to promote Wheeler's election

to Congress, not to consider Troup's proposed reappraisal of the settlers'

lands, the announced purpose. The delegates voted to refer the question

of appraisal back to the individual towns, and the meeting finally broke

up in an uproar. Seeing that nothing more would come of the convention,

farmers in various towns asked Troup to put the appraisal system into

effect, and he did so. Grattan Wheeler (who won the seat in Congress)

started doing the appraisal in the spring of 1831.

Party politics frustrated the mass protest movement against the Pulteney

Estate in 1830. However, political action did obtain two notable victories

for the settlers. State law required that all jurors and major town

officials be freeholders, that is, owners of real estate worth at least

$150. This requirement excluded a majority of the settlers on Pulteney

lands from holding office or serving on juries, since they had not yet

gotten deeds to their farms. In 1829 the Legislature passed a law exempting

Steuben County from the freeholder requirement, and substituted $150

worth of improvements on land under contract for sale. This permitted

a fuller exercise of democracy on the local level. Another political

struggle concerned taxation of debts owed to non-residents, such as

the Pulteney Estate and the Holland Land Company. For over twenty years

Assembly members from western New York worked for passage of such a

tax, and the land agents fought it each time such a bill was introduced.

A tax on debts owed to non-resident landholders finally became law in

1833. The Pulteney Estate had always paid taxes on its unsold lands.

Because of the many errors made by local tax assessors and collectors,

the land agents preferred to let the tax bill remain unpaid. In that

case, the State Comptroller would levy the correct amount of tax after

reviewing the property description and assessment data, and the Pulteney

land office would pay the tax that was due.

The anti-land office excitement of 1829-30 occurred just as the Pulteney

and Johnstone lands in Steuben County were beginning to sell fast. During

the 1830s and '40s the annual collections in the "Steuben Department"

(Steuben County and the easternmost tier of towns in Allegany County)

were usually double or triple what they had been in the depression years

of the 1820s. The Bath land office purchased new ledgers to record the

increasing number of conveyances recorded by the agency clerks with

their goose quill pens. The acreage sold (but not yet deeded) reached

a peak in the speculation year of 1836, just prior to the financial

panic of 1837. By 1840 about eighty per cent of the original Pulteney

lands had been sold. Initial sales of lots during the 1840s were only

a small fraction of what they had been in previous decades; almost every

lot was now under contract or deeded off. However, many contractors

were slow to pay the principal and interest they owed. The land agents

simply allowed many poor settlers to remain on their lots. In the mid

1830s the land office had brought several court actions to evict squatters.

There were few eviction cases after that, until a stricter policy was

adopted.

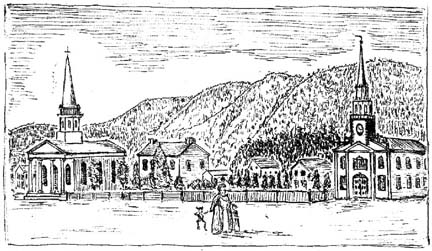

Redrawn from Barker & Howe’s Historical Collections

(1843) showing a view along

the east end of the row of buildings facing Pulteney Square across Morris

Street from the south.

On the right is the Presbyterian Church built in 1822, the first building

in the county with a steeple.

On the left is the Episcopal Church. (Editor’s note: Is the larger

building close to the Episcopal Church,

the Pulteney Land Agent’s Residence shown as #14 in the 1804 drawing

of the Village of Bath?)

In 1853 the Johnstone heirs of Sir William Pulteney appointed an Englishman

named William Brown as the new principal trustee for their American

properties. Brown concluded that the American real estate should be

producing more income for the Johnstone family. He directed the land

agents in Geneva and Bath, Joseph Fellows and William W. Young, to have

every lot under contract for sale surveyed and appraised. Caleb A. Canfield,

an insurance agent residing in Bath, was hired to visit each town to

collect money owed by settlers, so that they would not have to travel

to Bath. The land office sent out hundreds of printed circulars and

many dunning letters to delinquent contractors. These measures did produce

an increase in collections, particularly in the "Northern Department"

of the Pulteney and Johnstone estates (scattered tracts of land in Ontario,

Wayne, Livingston, and Monroe Counties). The increased collections still

did not satisfy Brown. In the fall of 1860 he travelled from England

to Bath to examine the accounts and affairs of the land office. He ordered

the land agents to press the settlers harder for the money they owed

and to prosecute defaulting debtors when they refused to pay anything,

even if they were able to do so. As a result, nearly fifty ejectment

suits were brought in Steuben County courts during 1861. Brown also

forced Joseph Fellows and William W. Young to resign as agent and sub-agent,

respectively, for the Johnstone Estate. They were replaced in the spring

of 1862 by Young's son, Benjamin F. Young, cashier of the Rochester

City Bank. Fellows continued as agent of the Pulteney Estate until 1871,

when he was obliged to retire from that post, at age 89.

At mid-century the lands still owned by the Pulteney and Johnstone

estates lay mostly in central and southern Steuben County. Many debtors

to the land office and sympathetic friends and neighbors protested the

new, stringent policies. Mass meetings (each attracting well over one

hundred persons) were held in Fremont, Howard, Canisteo, Hornellsville,

and Greenwood in the winter and spring of 1861 to discuss the situation.

The meetings declared that the poor farmers up in the hills could not

pay for their land because rust and midge had ravaged their wheat crops;

because the price of wool was low; and because their lots had nothing

but thin, stony soil that would never produce much anyway. They demanded

reductions in the price of lands. The land office at first took no public

notice of the meetings, but eventually Caleb A. Canfield attended some

of them to learn firsthand what was going on. The land agent meanwhile

proceeded with the ejectment suits. In one case the Steuben County sheriff

and an armed posse burned the house of an evicted settler in the town

of Howard. The settlers never forgot this cruel act.

The settlers opposing the Pulteney land office were generally called

"anti-renters." In fact they did not rent their farms but rather contracted

to purchase them. The term "anti-renter" was borrowed from the anti-rent

movement of the Catskill Mountain region, which had erupted in the 1840s.

There tenants of the Van Rensselaer family and other great landlords

fought successfully to have their rents reduced and the system of life

leaseholds abolished. By the fall of 1861 the leaders of the "anti-renters"

in Steuben County were meeting secretly in barns to discuss strategy

for the public meetings. They organized themselves into a "Home Diligence

Safety Society," whose president was Daniel Brownell of Fremont. The

members of the secret society swore not to reveal their conversations

and activities to anyone. Rumors spread that the angry settlers would

attack the land office on Pulteney Square in Bath, and the agents prudently

mounted iron shutters on the windows and the front door.

Opposition to the land office continued through the rest of the 1860s.

One form of resistance was refusal to pay contract debts; another was

intimidation of those who did pay. The letters from the land agent to

his principal in England indicate that refusal to pay did harm the Pulteney

heirs, for receipts fell markedly during the 1860s, despite high farm

prices during the Civil War. Intimidation had mixed results. During

1862 the anti-renters tried to recruit supporters in the town of Springwater,

Livingston County, but some farmers there refused to go along. In August

anti-renters from Howard and Fremont burned the barn and killed livestock

belonging to one Springwater farmer (named Mead) who was continuing

to pay for his land. They beat up another man (Alonzo Snyder) who was

doing the same. The Livingston County sheriff arrested several persons

and held them for trial on charges of arson and attempted murder. A

Fremont man who had been arrested for taking part in the attack on Snyder

was rescued by an "armed mob" while he was being taken to the Livingston

County jail. (Four men were eventually convicted for their part in that

affair.) A grand jury in Geneseo also handed down indictments against

27 other men. The Steuben County sheriff tried twice to arrest the men

who had been indicted. Both times residents of Fremont and Howard who

sympathized with the anti-renters assembled with weapons to prevent

any arrests. The cautious sheriff refused to try again.

Another violent incident occurred in 1864. When one man bought a Pulteney

lot in Fremont from which the previous contractor had been evicted,

a dozen or more anti-renters in masks came to his house one August night.

They broke down the door, smashed the furniture, beat up the farmer,

and raped his daughter. They demanded the land contract for the farm.

When he could not produce it, the ruffians bound and blindfolded him

and threatened to kill him if he did not get off the farm. Such brutal

acts won the anti-renters no friends. In 1867 a deputy sheriff tried

to sell some of the personal property of Edmund Butcher of Fremont,

an anti-rent leader, in order to satisfy a court judgment against him

in favor of the Pulteney Estate. An armed crowd of about two hundred

persons prevented the deputy from conducting the sale. The sheriff threatened

to get help from the National Guard to allow him to levy the judgment.

In the end he did nothing. The last reported incident of violence occurred

in 1872, when the sheriff's horse was shot while he was driving to a

farm in Howard to evict the occupant, an anti-renter. The $1,000 reward

offered for capture of the culprit was apparently never collected. The

sheriffs were reluctant to make arrests or levy judgments if it involved

the risk of personal injury. This reluctance was obvious to both the

land office and the anti-renters, and it helped the cause of the latter.

The land office held all the cards when the game concerned the legal

title of the Pulteney and Johnstone families, heirs of Sir William Pulteney.

Ever since the 1820s there had been repeated attempts to strike down

the Pulteney title, and every one failed. For example, in 1840 the New

York Attorney General had reported that "every link in this title [of

the Pulteney Estate] is complete and perfect." During the 1860s the

anti-renters tried again. In the fall of 1861 and again in 1862 Henry

Sherwood of Corning was elected to the New York State Assembly on an

"anti-rent" platform. He got a seat on the Assembly judiciary committee

and worked for repeal of an 1821 law confirming the legal title of the

Pulteney heirs. The repeal bill passed the Assembly two years in a row,

and failed to pass the Senate only because the land agent sent Caleb

A. Canfield to Albany to lobby against it. After this legislative effort

failed, the anti-rent leaders persuaded the state attorney general to

bring an ejectment suit against Alonzo Snyder of Springwater. The aim

was to test the Pulteney title in the courts. (This was the same Snyder

whom the anti-renters had harassed in the summer of 1862.) This court

action commenced in 1864 and dragged on for years while the anti-rent

party made pretense of obtaining "proof" that Charles Williamson, first

agent of Sir William Pulteney, was never a naturalized American citizen.

In fact the land office had in its safe Williamson's original signed

certificate of naturalization, dated 1792. Many debtors to the land

office held off paying any more on their contracts, waiting to see how

the lawsuit turned out. The case was decided against the anti-renters

twice in the Supreme Court. It finally went to the Court of Appeals,

which again upheld the Pulteney title in 1868.

The anti-renters in the hill towns had considerable public sympathy

at first, but support dwindled after the incidents of violence. The

land agent believed that many of the people who attended the anti-rent

meetings were merely "curious," and this may have been correct. However,

in some towns the opposition to the land office was real and deep. There

the anti-rent movement persisted for a decade, even though its legal

position was weak. Unfortunately the politicians who courted the anti-rent

vote were more concerned about their own careers than about the unjust

policies of the land office. In the legislative session of 1863, two

of the three Assembly members from Steuben County, Horace Bemis and

Henry Sherwood, both Republicans and professed "anti-renters," told

Canfield privately that they wanted their bill to pass the Assembly

merely to satisfy their constituents. They admitted that they did not

care if it failed again in the Senate, as it had the year before, because

its passage in the Assembly would ensure their return to Albany in the

next election. Sherwood even solicited a bribe from Canfield in return

for a promise to block passage of the bill in the Senate. Canfield refused

the offer. There was treachery in the land office as well. In December

1867 land agent Benjamin F. Young discovered in the office a petition

from the settlers to the trustees of the Johnstone Estate, seeking reduction

of their debts. The document was in Canfield's handwriting. In fact

he had been secretly sympathetic to the settlers' cause for several

years. Because of his disloyalty and duplicity, Canfield was immediately

fired.

The Pulteney Land Office after 1867

This building was the Bath Hospital from 1910 to 1916 and was torn down

in 1920.

(Editor’s comment: The darker brick work on the right side suggests

that this building might have

been enlarged from a three-window-wide building to a building with five

windows in front.

Photograph supplied by the Steuben County Historical Society.

The Pulteney-Johnstone land office certainly did have a policy of patience

with settlers who could not keep up with their payments. This patience

verged on laxness during the long tenure of Joseph Fellows as principal

agent of the Johnstone Estate (1832-1862). His obituary states that

he was always scrupulously honest, but that "he was not a systematic

businessman." However, prudent investment of his enormous annual salary

of $5,500 a year plus commissions on land sales made him a wealthy man.

William Brown, the English trustee, wrote that Fellows' administration

of the estate had been characterized by "gross neglect" in the collection

of debts. Yet even under the stricter administration of the early 1860s,

the new land agent still admitted that "coercion" of the settlers did

little good. Public opinion was against it, and anyway the debtors to

the Pulteney Estate were too poor to pay much. Even when farm prices

climbed during the later years of the Civil War, there remained a "large

number" of settlers "who produce merely enough for their support and

cannot make payments on their debts." Many of those settlers had paid

nothing for so long that their lands were considered to have reverted

to the Pulteney Estate. Therefore the land office did not have to pay

the personal property tax on those land contracts. Legally such settlers

were squatters, liable to eviction.

Canfield remarked in a letter to the land office in 1860 that "the

sooner this class of settlers are disposed of, the better for the county

as well as for the estate. Most of them can be got rid of without much

trouble. A few will require legal measures." This statement was not

so callous as it sounds. Much of the land in the anti-rent towns was

hardly worth farming, and some of those who stayed on such farms simply

lacked the ambition to get out. A well-off Fremont farmer thought that

his anti-rent neighbors should have spent their time and energy improving

and paying for their farms, rather than fighting the land office and

worrying about being evicted. In any case, the Pulteney and Johnstone

estates were rapidly shrinking as its remaining lands were deeded off

during the years following the Civil War. Attorney Frederick Y. Wynkoop

of Bath took over management of the land office in 1883. He bought the

few remaining lots in 1903, ending a century of the Pulteney family's

ownership of lands in Steuben County. The board of supervisors appropriated

$300 in 1909 to purchase "papers, field notes, books, records, maps,

etc., formerly belonging to the Pulteney Estate, and now in their vaults

at Bath." (Not purchased were records and papers "of a purely financial

nature.")

The final verdict on the administration of the Pulteney Estate need

not be left to employees of the land office or to well-off farmers who

may not have fully appreciated poor men's problems. Two prominent Bath

attorneys writing in the 1850s found the Pulteney and Johnstone heirs

and their agents guilty of a narrow, mean policy that ignored the plight

of the settlers and hindered the development of Steuben County. William

Howell noted that most of the settlers were "poor people" who were attracted

to the Pulteney lands by the deceptively easy terms of payment—no

money down, many years to pay. But few settlers were ever able to pay

more than the interest on their land contracts. Howell asserted that

the land agents grew rich while most of the settlers "left the country

[county], cursing the policy and system of business which had been adopted

by the owners."

Guy H. McMaster wrote in his History of the Settlement of Steuben

County (1853) concerning the Pulteney heirs: "So long as they are

content to confine their claims to consideration to their character

as sellers of land, it must be admitted that they have conformed to

the rules of common dealing amongst men. But if, beyond this, they should

have the effrontery to lay claims to public gratitude for services rendered

to the county in its days of toil and privation, or should demand credit

for liberality in the administration of the affairs of the estate .

. ., these pretensions would be simply preposterous. We do not know

that any such claims are put forth. The only concern of the proprietors

has been to get as much money as it was possible to get, and whether

settlers lived or starved has not, so far as human vision can discern,

had a straw's weight in their estimation." McMaster conceded that certain

individuals employed in the land office may have performed acts of kindness

to the settlers. But in general, he concluded that "the alien proprietorship

deserves no thanks from the public, and probably will never think it

advisable to ask for any. It has been a dead, disheartening weight on

the county. The undeniable fact [is] that a multitude of hard-working

men have miserably failed in their endeavors to gain themselves homes—have

mired in a slough of interest and installment, leaving the results of

their labors for others to profit by." The young historian (McMaster

was only 24) concluded by expressing wonder that the settlers had never,

up to that time, engaged in violent resistance to the British proprietors—"foreign

lords of immense tracts of land in a country heartily hostile to everything

savoring of aristocracy."

An 1861 Photograph of Buildings in Bath

along the South Side of Morris Street Facing Pulteney Square

The Presbyterian Church, built in 1822, appears centered on

the walkway running across the square, and is probably aligned on Liberty

Street. The residence with the many steep gables was owned by James Lyon.

The buildings on the right side of the photograph are the residence of

the Pulteney land agent, and the Land Office. A connection between them

is visible. (Editor’s comment: The larger building with what appears

to be a signboard in the pediment above the four-column portico looks

to be a building for public business. This building may be on the location

of the 1867 Land Office. Could it and the structure close behind on the

right, to the building’s left, have been enlarged and remodeled

to the later land office?) The picture was provided by the Steuben County

Historical Society with a scanning made by Nedra McElroy from the original

photograph.

Organized resistance to the Pulteney land office finally developed

because the British owners held on to their American lands and did not

sell out to local investors. (The Holland Land Company, the Dutch syndicate

which owned most of far western New York, had sold out in the 1830s.)

There was real substance to the frequent complaints that the Pulteney

land office took money out of Steuben County, impeding its economic

growth. From the mid-1820s through the late 1840s the Pulteney land

office almost every year collected in its "Steuben Department" more

than double the total Steuben County property tax levy. Though a portion

of the land office receipts stayed in the county to pay taxes and cover

salaries and office expenses, most of the money went to the Pulteney

and Johnstone families in Great Britain. It is no wonder that even conservative

lawyers who respected property rights could find little good to say

about the policies of the absentee landowners. There were certainly

geographic reasons for Steuben County's slow start. But major responsibility

could be laid on individuals—the calculating land agents and grasping

British aristocrats. They were not easy to love.

Bibliography

The following bibliography lists works used for this history of the Pulteney

Estate during the nineteenth century, as well as other works relating

to the Genesee lands and Charles Williamson's land agency during the 1790s.

Published Works

Barbara Chernow. "Robert Morris: Genesee Land Speculator."

New York History, 58 (1977), 194-220.

Henry Christman. Tin Horns and Calico: An Episode

in the Emergence of American Democracy. New York: 1945. (History

of the "anti-rent" controversy in eastern New York.)

W. Woodford Clayton, ed. History of Steuben County,

New York, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its

Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia: 1879; repr. Bath: 1976.

(Contains transcripts of documents relating to the controversy between

the settlers and the Pulteney Estate, 1829-1830, pp. 81-86.)

George S. Conover. The Genesee Tract. Cessions between

New York and Massachusetts; The Phelps and Gorham Purchase; Robert Morris;

Captain Charles Williamson and the Pulteney Estate. Geneva: 1889.

Helen I. Cowan. Charles Williamson: Genesee Promoter-Friend

of Anglo-American Rapprochement. Rochester: 1941; repr. Clifton,

N.J.: 1973.

__________. "Charles Williamson and the Southern Entrance

to the Genesee Country." New York History, 23 (1942), 260-74.

__________. "Williamsburg, Lost Village on the Genesee."

Rochester History, no. 4 (July 1942), 1-24.

Horst Dippel. "German Emigration to the Genesee Country

in 1792: An Episode in German-American Migration." Germany and America:

Essays on Problems of International Relations and Immigration, ed.

Hans L. Trefousse. New York: 1980. (Essay is found on pp. 161-69.)

Lockwood R. Doty, ed. History of the Genesee Country,

4 vols. Chicago: 1925. (Chap. 12, Charles F. Milliken, "Phelps and Gorham

Purchase," pp. 351-88; Chap. 49, Reuben Oldfield, "Indian Myths and Legends

with an Historical Narrative of Steuben County," pp. 1241-1309, contains

transcripts of some Pulteney land office correspondence, 1804-1811.)

Kline D'A. Engle. "The Williamson Road." Proceedings

of the Northumberland County [Pa.] Historical Society, 12

(1942).

Paul D. Evans. The Holland Land Company. Buffalo:

1924.

__________. "The Pulteney Purchase." Quarterly Journal

of the New York State Historical Association, 3 (1922), 83-104.

Julius Goebel, Jr., and Joseph H. Smith, eds. The

Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton: Documents and Commentary, Vol.

3. New York: 1980. (Expert discussion of Williamson's legal dealings,

for which Hamilton was his attorney, pp. 758-812.)

Alfred G. Hilbert. "The Williamson Road." Crooked

Lake Review, no. 64 (July 1993), 1, 13-14, no. 65 (Aug. 1993), 13-14,

17, no. 66 (Sept. 1993), 11-14.

Guy H. McMaster. History of the Settlement of Steuben

County, N.Y. Including Notices of the Old Pioneer Settlers and Their Adventures.

Bath: 1853; repr. Geneva: 1893; Bath: 1975.

Neil A. McNall. "John Grieg: Land Agent and Speculator."

Business History Review, 33 (1959), 524-34.

Howard L. Osgood. "History of the Title of the Phelps

and Gorham Purchase." Publications of the Rochester Historical Society,

1 (1892), 19-51.

A. J. H. Richardson and Helen I. Cowan, eds. "William

Berczy's Williamsburg Documents." Publications of the Rochester Historical

Society, 20 (1942), 139-265.

Millard F. Roberts, comp. Historical Gazetteer of

Steuben County, New York. Syracuse: 1891; repr. Bath: 1979.

George Roach, ed. "Documents: Johnstone-Troup Correspondence."

New York History, 23 (1942), 57-68. (Prints letters from 1809-1811

concerning economic conditions in Steuben County.)

Sherman S. Rogers. Address . . . Delivered at Bath,

N.Y., June 7, 1893, at the Centennial Celebration. Buffalo: n.d.

Robert W. Silsby. "Mortgage Credit in the Phelps-Gorham

Purchase." New York History, 41 (1960), 3-34. (Summarizes findings

of dissertation, cited below.)

Lorne R. Smith, comp. A Story of the Markham Berczy Settlers:

200 Years in Markham, 1794-1994; A Story of Bravery and Perseverance.

Markham, Ont.: 1994. (Summarizes careers of Wilhelm Berczy and his German

settlers after their arrival in Canada.)

William M. Stuart. Stories of the Kanestio Valley,

3d ed. Dansville: 1935; repr. Canisteo: 1978. (Discusses the anti-land-office

movement, pp. 180-89.)

Orsamus Turner. History of the Pioneer Settlement

of Phelps and Gorham's Purchase, and Morris' Reserve. Rochester:

1851; repr. Geneseo: 1976.

Robert W. G. Vail. "The Lure of the Land Promoter: A

Bibliographical Study of Certain New York Real Estate Rarities." University

of Rochester Library Bulletin, 24 (1969), 33-97. (Discusses Robert

Morris's promotional publications for the Genesee Country.)

__________. The Voice of the Old Frontier. Philadelphia:

1949. (Discusses Charles Williamson's anonymous promotional pamphlets,

cited below; pp. 438-39, 449.)

__________. "A Western New York Land Prospectus." Bookmen's

Holiday. New York: 1943. (Discusses Williamson's 1804 promotional

pamphlet, cited below, in its various editions.)

John. G. Van Deusen. "Robert Troup: Agent of the Pulteney

Estate." New York History, 23 (1942), 166-80.

Charles G. Webb. "The Williamson Road." Now and Then:

Quarterly Magazine of History, Biography and Genealogy (Muncy, Pa.),

10 (1953), 190-205.

[Charles Williamson.] Description of the Settlement

of the Genesee Country in the State of New-York. In a Series of Letters

from a Gentleman to His Friend. New York: 1799. Repr. in Documentary

History of the State of New-York, octavo ed., 2:1127-68. Albany:

1849.

[Charles Williamson, pseudonym "Robert Munro."] A

Description of the Genesee Country, in the State of New-York. New

York: 1804. Repr. in Documentary History of the State of New-York,

octavo ed., 2:1169-89. Albany: 1849.

Clarence Willis. Pulteney Land Title; Genesee Tract;

Together with the Illustrations of Characters Prominent in the Colonization

and Settlement of Western New York, 5th ed. Bath: 1927. (First edition

was published in 1910.)

Dissertations and Other Unpublished Works

James D. Folts. "Guide to Records of the Pulteney Estate,

Steuben County Clerk's Office, Bath, N.Y.," typescript, 1981.

William Howell. "Steuben County: Its Settlement and Early

History," undated typescript copy of lost manuscript, probably ca. 1850

(University of Rochester Library).

Ernestine E. King. "Some Observations on the Joseph Fellows

Papers," typescript, 1965.

Robert W. Silsby. "Credit and Creditors in the Phelps-Gorham

Purchase." Ph.D. Dissertation, Cornell University, 1958. (Study of land

economics in Ontario and Steuben Counties, 1789-1820, focusing on policies

of the Pulteney land office and other creditors.)

Wendell E. Tripp, Jr. "Robert Troup: A Quest for Security

in a Turbulent New Nation, 1775-1832." Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University,

1973.

Newspapers

NOTE: This listing of newspaper references to the Pulteney

Estate and its land agents is selective.

Ontario Repository (Canandaigua), Dec. 5, 1809.

Steuben Patriot (Bath), Feb. 27, 1823.

Steuben Farmer's Advocate (Bath), May 19, 1825,

Apr. 10, 1828, Jan. 28, Feb. 11, Apr. 22, May 13, July 29, Nov. 18, 1830

(and several other issues), June 25, 1862, Aug. 12, 1868, May 2, 1873

(obituary of Joseph Fellows).

Steuben Courier (Bath), May 14, 1856, Aug. 24,

1864, May 29, 1867, Nov. 30, 1870, Jan. 31, Sept. 18, Nov. 20, 1872, June

20, 1884 (obituary of Frances Cameron, widow of Dugald Cameron).

Plain Dealer (Bath), June 19, 1886, Dec. 22,

1888.

Pulteney Land Office Records

NOTE: Most of the Pulteney Land Office records held

by the Steuben County Clerk's Office have been microfilmed. Copies of

the microfilm are held by the Steuben County Clerk's Office in Bath, the

Corning Area Public Library, and the New York State Archives in Albany.

See Folts. "Guide to Records of the Pulteney Estate" (1981), cited above,

for a guide to the records and the microfilm.

The following volumes were used for this history

of the management of the Pulteney Estate during the nineteenth century:

Letter Book no. 1, 1801-1812, Cornell University Library.

Letter Book no. 3, 1804-1808, Steuben County Historical

Society.

Letter Book no. 4, 1808-1815, Steuben County Clerk's

Office.

Letter Book no. 7, 1819-1824, Steuben County Clerk's

Office.

Letter Book, 1859-1862, Steuben County Clerk's Office.

Letter Book, 1862-1895, Steuben County Clerk's Office.

Abstract of Lands and Debts, Steuben Department, 1861-1862,

Steuben County Clerk's Office.

Other Manuscripts

Joseph Fellows Papers, private collection.

Howard L. Osgood Papers, Rochester Public Library (includes

an abstract of yearly land sales and collections in the "Steuben Department"

of the Pulteney Estate for the years 1820-1848).

George J. Skivington Papers, Rochester Public Library.

Statutes

N.Y. Laws of 1821, Chap. 19.

N.Y. Laws of 1829, Chap. 18.

N.Y. Laws of 1833, Chap. 250.

Legislative Documents

N.Y. Attorney General. "Report of the Attorney General,

Relative to the Title of the Trustees of the Pulteney Estate to Lands

in Steuben and Allegany Counties." Assembly Document no. 342, 1840. (Detailed

report and opinion upholding soundness of the Pulteney title.)

N.Y. Legislature. Assembly. "Report of the Select Committee

on the Petitions of Sundry Citizens of Steuben County, in Relation to

the Pulteney Estate." Assembly Document no. 121, 1847.

N.Y. Legislature. Assembly. Judiciary Committee. "Report

of the Majority of the Committee of the Judiciary, on the Petitions of

Citizens of the Counties of Steuben and Allegany, for Repeal of Chapter

19 of the Laws of 1821, Relative to the Title of the Pulteney Estate in

This State." Assembly Document no. 141, 1862. (Committee majority, including

two of Steuben's three Assembly members, argued that the act of 1821 confirming

the Pulteney title was invalid.)

N.Y. Legislature. Assembly. Judiciary Committee. "Report

of the Committee of the Judiciary Relative to the Pulteney Estate." Assembly

Document no. 204, 1862. (Committee minority argued that overturning a

sound title would cause needless trouble.)

Case Reports

Duke of Cumberland v. Graves, 3 Selden's Reports 305.

Duke of Cumberland v. Codrington, 3 Johnson's Chancery

Reports 229.

Howard v. Moot, 64 N.Y. Reports 262.

People v. Alonzo Snyder, 41 N.Y. Reports 397.

|