|

The Cardiff Giant

Lives on in Legend

by

One of the biggest hoaxes ever perpetrated on the general public was

conceived by a group of people, one of whom was David Hannum, known more

commonly as David Harum of Homer fame.

Although its creators are long deceased, the legacy of the "petrified

man," known as the Cardiff Giant, lives on, and is a center of attraction

at the Farmers' Museum in Cooperstown.

On October 16, 1869, workmen unearthed a 10½-foot tall stone giant on

the farm of Stub Newell in Cardiff, a rural area in southern Onondaga

County not far from LaFayette. This spot, coincidentally, was the site

of the famous 1993 mudslide that destroyed several homes.

The find created a sensation so great that it even caught the attention

of the renowned P. T. Barnum. He attempted, unsuccessfully, to purchase

the Cardiff Giant and capitalize on the find. The male figure was carved

from gypsum and was the subject of a facetiously written booklet entitled

"Autobiography of the Great Curiosity the Cardiff Giant."

The story of the Cardiff Giant is an example of how the general public

can be duped into believing anything by a convincing argument, at which

Barnum was a master. It is said he coined the phrase, "There's a sucker

born every minute."

The idea of the Cardiff Giant originated with George Hull, a Binghamton

businessman. He was visiting relatives in Iowa, and one night, while reading

the Bible, he thought to himself, if people believed everything they read

there about giants roaming the earth, he would produce one and pass it

off as a petrified man, and get rich.

After an extensive search, he found a suitable outcropping of gypsum,

gray in color, with dark-colored bluish streaks, which he afterward passed

off as veins of a human body. Hull hired a gang of men to cut out a block

of gypsum 11 feet, 4 inches long, 3 feet, 6 inches wide, and more than

two feet thick.

The block was then transported by wagon 45 miles to the nearest railroad

station at Boone, Iowa, where it was loaded into a boxcar and shipped

to Chicago. There, Hull rented a building and had a stone cutter shape

the block into a man's image.

To give it some authenticity, Hull made a tool resembling a hair brush,

into which he inserted darning needles. He then ran it over the statue,

pitting it with thousands of little holes to resemble skin pores. Hull

then swabbed the body with sulfuric acid which gave the stone a dingy

brown color. He recalled, "Then I put the giant in an iron-bound box and

shipped it by rail to Union, nine miles from Binghamton." Packaged it

weighed 4,000 pounds.

Because many petrified fish and reptiles had been discovered there over

the years, Hull said he decided to have the giant buried on a farm near

Cardiff. The area was once covered by a lake in prehistoric times. Hull

was related to Stub Newell.

In the dead of night the giant was unloaded from a boxcar at Tully, and

taken by wagon to the Newell farm. At midnight, in the pouring rain, it

was placed in the back of Newell's barn and covered with hay and straw.

A few nights later, it was buried in a "grave" nearby. "Indeed it was

no small job to remove all trace of the midnight burial," Hull said.

On Saturday, October 16, 1869, according to a pre-conceived plan, Newell

hired some men to dig a well behind the barn-—coincidentally where

the giant lay buried. One can only imagine the expression on their faces

when they unearthed the giant. What followed was a scenario that developed

into one of the greatest hoaxes of the 19th century.

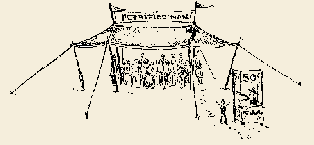

Newell set up a tent and charged 50 cents admission. It is said he made

more money in a month than he did all year long farming on a rocky hillside—even

after splitting the proceeds with Hull, Hannum and other investors who

had purchased shares in the fraud.

Triple rows of spectators surrounded the excavation for days. Even the

state geologist and a party of scientists certified, after careful examination,

that the petrified man was authentic.

It took a young paleontologist from Yale University, O. C. Marsh, to

expose the fraud. When he revealed that the giant was nothing more than

a piece of gypsum, the hoax unraveled into a scandal.

Thus, from a household word of being the greatest scientific discovery

of the 19th century, the Cardiff Giant fell to the level of a sideshow

curiosity. But the Giant continued to be a good investment as it was exhibited

all over the country.

Over the years, the Giant passed through several owners, including a

syndicate known as the Cardiff Giant Association. It eventually made its

way back to Iowa, where it became a curiosity in a rumpus room. In the

1940s it was brought to the attention of the New York State Historical

Association and was brought back east to become an exhibit at the Farmers'

Museum, where it continues to draw the attention of visitors.

An anecdote is told of David Hannum's connection with the Giant. One

day in the 1870s he boarded a train in Homer bound for Syracuse and was

seated when approached by a dapper looking young man named P. Elmendorf

Sloan, who at the time, was superintendent of the Syracuse & Binghamton

Railroad. Hannum was a large man and took up most of two seats. Sloan

asked him to move over, but Hannum refused.

"See here," Sloan said, "do you know who I am? My name is Sloan and my

father, Sam Sloan, is president of this railroad."

"See here," Hannum retorted, "do you know who I am? My name is David

Hannum and I'm the father of the Cardiff Giant."

|