|

Genesee Vignettes

Personal Reflections on the Genesee River

A series of eighteen essays by

X. Moving Further Upstream

In mid-August 1986 Dad flew into Rochester, on his way to visit Grandma

Cornell. As planned, he spent the night with me and the next day we drove

to Campbell together. Also as planned, we left my apartment early enough

for a side trip. Our route took us through Letchworth, where we stopped

briefly at the Middle Falls.

But our main aim was to locate family grave sites in Belfast, New York,

on Route 19 south of Letchworth. Here we struck out. Although we succeeded

in locating the village cemetery, our quick search turned up no familiar

names. With time now running short, we pushed on to Campbell.

Several days later, I returned to pick Dad up, and before we left, Grandma

agreed to show us the location of the tombstones we had missed. Reversing

our earlier steps, we followed Route 17 (now 1-86) west to the Route 19

exit and then north to Belfast. At the cemetery Grandma took us right

to the stone for Margaret Beard, her father's great grandmother.

Back in the car, we continued down the side street and soon reached the

river. After crossing the bridge, we turned south—which put us onto

a country road that paralled Route 19 (with the Genesee now between us

and Route 19). A few miles later we reached a small cemetery, one that

Dad and I would never have found without Grandma's help. There she showed

us the stones for Cornelius Hopper and Hannah Rockwell Hopper—her

mother's mother's mother's parents—along the following line:

Beatrice Marie Beard

daughter of

Myron Alonso Beard m. Lena Delphine Emerson

daughter of

Charles Kent Emerson m. Hannah Jane Owen

daughter of

Frederick Owen m. Mary Hopper Bennit

daughter of

Cornelius Hopper m. Hannah Rockwell

On this visit, as well as on subsequent visits, I learned how Grandma

had worked out her line back to Cornelius Hopper—which hadn't been

easy. At first, the things she knew had come solely from her family's

oral tradition. She could talk at length about her own mother, and she

knew many things about her mother's mother. But the only significant thing

she knew about her mother's grandmother was that she had been a founding

member of the Baptist Church at Altay, New York. For the lines of descent

further back, the oral tradition was silent. Grandma didn't even know

the family name.

Discovering that surname was an exciting achievement, because it opened

up new routes for her genealogical research. In its fullest form the story

began with an invitation from two of her genealogical society friends,

Bernice Lyon and Evalena Stickler, to visit a museum near Ithaca, New

York.8 On their trip they stopped for lunch at the home of

Mr. and Mrs. Finch. Jessie Everts Howell Finch, formerly of Elmira, New

York (where the Howell family owned a publishing company), was an active

genealogist who had published genealogical books. As Grandma and her friends

were leaving, Mrs. Finch said, "Oh, wait a minute." She then gave them

a copy of her book on the Howell family.

Not until several months later did Grandma take the book from her bedroom

shelf and begin looking through it. Quite unexpectedly, she found that

it mentioned her mother's grandparents: "Frederick Owen and wife Mary

of Wayne."9 Even better, it identified Mary as being the daughter

of Cornelius and Hannah Hopper. "That's how I got started on [researching]

the Hoppers," Grandma told me.

Her earliest work emphasized Cornelius's father, Matthew. Although she

never actually did so, she said she could have applied for a supplemental

DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) line to him, and on one occasion

she and I looked up his name in a book on New York in the Revolution—which

listed him as a citizen of New York City from whose house, window lead

had been taken for use by the army.10

Grandma did use Matthew Hopper to apply for a supplemental DAC (Daughters

of the American Colonists) line. But more importantly, his service during

the French and Indian War enabled her to apply for membership in a third

genealogical society. In 1968 she joined Daughters of Colonial Wars, based

on a published muster roll that listed him as having joined the New York

militia in 1759.11

In all this, my own interest tended to follow Cornelius Hopper. On a

family visit in the late 1960s I had learned from Grandma that he had

served on the Sullivan Expedition of 1779. After the Revolution he had

moved to the Elmira area, where his son Rockwell was born. Later the family

had moved further west, to the Belfast area—which is how Cornelius

and his wife came to be buried in Chamberlain Cemetery, between Belfast

and Transit Bridge.

"Did I ever tell you how I found that cemetery?" Grandma once asked me,

as a way of continuing her story.12 "The Allegany County Historical

Society—to which I paid dues for many years—published a monthly

newsletter, and I submitted to it an inquiry about the burial place of

Cornelius Hopper. I soon received a reply from a woman who had found his

tombstone. Later Ben and Zibbie Look [friends in Campbell] went with me

there and to the cemetery in Belfast, where we had a picnic."

After Grandma's death, material relating to her Hopper research surfaced

in her papers. On the whole, the documents confirmed the stories she had

told me. But her stories had always possessed the smooth contours of a

genial grandmother's talk with her eager grandson. By contrast, the documents

testified to the more highly textured surfaces of her adult personality.

Consider, for example, the correspondence associated with her newsletter

inquiry. She had first written the county historian toward the end of

October 1969, passing along the relevant information and asking about

the burial place of Cornelius and Hannah Hopper. A month later he reported

the results of his research, as well as his plans to include Grandma's

inquiry in the next newsletter. Within a few days, Grandma sent him a

note of thanks. But she also gently scolded him for doing work she hadn't

asked him to do. "I am wishing to find only one thing," she emphasized,

"—the place where Cornelius and wife are buried."13

In early February 1970—after the newsletter had appeared and Grandma

had learned the location of the cemetery—she again wrote. "The score

is high," she opened, "for the 'Newsletter . . . ,' for you the Allegany

Historian, and for [the person who responded]."14 Having offered

words of praise, she then provided something of an apology. What had made

her earlier search so "tedious," she explained, was her initial assumption

that the cemetery lay in Caneadea Township. During the nineteenth century,

however, Caneadea Township had been partitioned, so that the Hopper residence

became part of Belfast Township. "Guess I shall never learn the lesson

which history researchers should learn," she concluded, "about partitions

of towns, etc."

Grandma's letters also demonstrated her awareness of the mismatch that

could arise between her interest in a subject and the interest of others.

From my own contact with her I knew how excited she could become when

describing the results of her research, and I've seen similar excitement

expressed in her correspondence. For example, in 1974 she wrote to one

of her genealogical society acquaintances:

I am sending you a page of cemetery inscriptions from Allegany

co., containing names of Cornelius and Hannah. One of the best, most rewarding

research trips I have ever made was made that day with friends here, June

17, 1970.15

But Grandma also worried about how receptive her audience would be. Thus

after describing her Hopper research in a draft letter to another acquaintance,

she cut herself short with the admission: "May already have bored you

too far."16

Regardless of the interest that others might (or might not) express in

her genealogical research, Grandma continued doing it. Through Cornelius

Hopper's mother she developed a line of Dutch ancestry to Cornelis Kuyper

(which she submitted as a supplemental DAC line):

Cornelius Hopper m. Hannah Rockwell

^

Matthew Hopper m. Aeltje Kuyper

^

Dirck Kuyper m. Cattelintie Van Pelt

^

Cornelis Kuyper m. Aeltje Bogart

Most important of all—in Grandma's eyes—was her line through

Hannah Rockwell Hopper. In early 1972 the result was an application to

join yet another genealogical society, Women Descendants of the Ancient

and Honorable Artillery Company. The line she submitted was as follows:

Cornelius Hopper m. Hannah Rockwell Hopper

^

Jonathan Rockwell [III] m. Hannah Bennett

^

Jonathan Rockwell [II] m. Esther __________

^

Jonathan Rockwell [I] m. Abigail Camfield

^

Samuel Camfield m. Sarah Willoughby

^

Francis Willoughby m. _______________

Although her application was accepted, Grandma was later mortified to

discover that she had made a fundamental error. The line was correct all

the way back to Samuel Camfield. But Grandma wasn't descended from Sarah

Willoughby—who turned out to be Camfield's first wife. Instead,

Grandma was descended from his second wife.

Meanwhile other events and circumstances intervened. The 1972 flood,

her "numb spell" a few years later, and her decreasing mobility due to

increasing old age: all these disrupted her research. Yet she persevered.

The result in 1984 was a successful application to join one final genealogical

society, Descendants of Founders of New Jersey.

The line she submitted ran to Matthew Camfield, the father of Samuel

Camfield, who was an early settler of Newark, New Jersey. The original

application still included the error, but soon thereafter Grandma reported

the correction:

Samuel Camfield m. Elizabeth Merwin

^

Matthew Camfield m. Sarah Treat

Thus on my visits after moving to Rochester, I was likely to find Grandma

wearing the pin of the society she had so recently joined and all set

to tell me the story of her research:

XI. A Day Trip along the Upper Genesee

In April 1994 Terry and I took a day trip along the upper Genesee. RIT's

Spring Quarter was still in session, but I had just handed back mid-terms—which

meant that I had a Saturday free. We took I-390 to Mount Morris and then

Route 408 south to Nunda, New York. Most of the way we talked about matters

relating to our life in Rochester. By Nunda, however, both of us were

ready to pay more attention to the countryside.

Although spring greens had begun replacing winter grays, the trees hadn't

yet leafed out. That made it easy to spot the historical marker along

Route 436, just west of Nunda. Yellow letters on a blue background proclaimed

to highway travelers:

HERE BEGAN THE 17 LOCKS

THAT LIFTED THE GENESEE

VALLEY CANAL OVER THE HILL

TO PORTAGE

Sure enough, as we continued our drive we could see—in the woods

to our right—the stonework from several of the locks.

Begun in 1836 to connect the Erie Canal at Rochester with the Allegheny

River at Olean, New York, by 1840 the Genesee Valley Canal had been completed

to Mount Morris. Progress was then slowed by the climb referred to in

the historical marker. Not until the early 1850s did the canal reach the

upper Genesee, and not until 1862 was its full length (124 miles) opened

for traffic. By then, however, railroads had eclipsed canals in importance.

As a result, in 1878 the Genesee Valley Canal was closed, and a railroad

was built along its towpath. Still later, automobiles eclipsed railroads—and

the towpath railroad was closed.

At Portageville, we crossed the river on the highway bridge. Just downstream,

two stone piers—the sole remnants of the canal aqueduct and railroad

bridge—arose from the slate green water, like sentinals from the

past. But as we headed south on Route 19A we kept a lookout for a new

use to which a portion of the old right-of-way has been put. A few hundred

yards beyond the turnoff to Whiskey Bridge (another bridge over the Genesee),

we noticed a sign bearing the distinctive logo of the Finger Lakes Trail.

Here we made our first stop of the day. As we hiked a short distance

along the old canal towpath and railroad grade, we could hear a tractor

in the field between us and the river. Meanwhile, in the trailside woods

we sighted another harbinger of spring: the fresh green leaves of new-sprung

skunk cabbage.

We didn't hike long. This was meant to be a day of "land research," scouting

out the terrain. At Houghton we took a short drive through the college.

At Caneadea I wondered if we'd find an historical marker for the Seneca

council house that had been moved to Letchworth—but no such luck.

At Belfast I showed Terry the cemetery I had visted with Dad and Grandma.

I also planned to show her Chamberlain Cemetery. But first we continued

along Route 19. I wanted to see if the cemetery was visible at a distance,

and when it came into view we stopped for a picture.

Although the river still flowed through a well-defined valley, the hills

now rose to only modest heights. Even the canal had made its exit—following

Black Creek (just upstream from Belfast) toward the Allegheny watershed.

We crossed the Genesee on Transit Bridge and reached Chamberlain Cemetery

from the south. The day was nice enough for a picnic, so we spread out

a blanket at the edge of the cemetery, with the Hopper tombstones in full

view (the pair in the foreground, at left):

Right away Terry noticed that Cornelius Hopper's had features that set

it apart from more recent tombstones. Not only did fossils appear on its

surface, but all its lines and letters were the obvious product a craftsman's

hand-eye coordination.

When Cornelius died—on 21 February 1814—the U. S. was still

fighting Great Britain in what amounted to a second war for independence.

The U. S. would emerge from the War of 1812 with its political sovereignty

firmly established, thus paving the way for a century of internal developments—notably,

its expansion westward across the continent and the transformation of

its economy, from agricultural to industrial.

Hopper's tombstone stands at the brink of both trends. When we think

of "Manifest Destiny," we often think of the Midwest and Far West. But

the tombstone is located where it is because Cornelius and his son Rockwell

helped settle the earlier "West" of the upper Genesee. In 1812 Cornelius

purchased an 85-acre tract from an agent of the Holland Land Company,

and the following year he deeded half of it to Rockwell. The result was

a farm along the eastern riverbank and later a successful "public house"

along the road.17

Where the tombstone's location bespeaks the "before" picture of Manifest

Destiny, its lettering bespeaks the "before" picture of machine production

and the factory system. So handmade is its appearance that the lettering

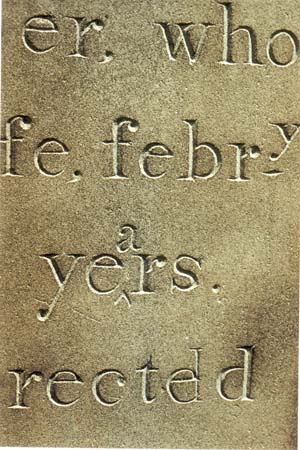

has more the feel of a penciled first draft than a polished typescript:

a small "4" in "1814" has been enlarged; to the misspelled "years," the

omitted "a" has been added; and instead of an abbreviated "erect'd," the

craftsman apparently decided—midway in the process—to spell

out the whole word:

Our picnic now over, we returned to Route 19. The drive through Belvidere,

Belmont, and Scio, New York—all south of the Southern Tier Expressway

(Route 17; I-86)—was new to me. But we didn't stop until we reached

Wellsville, New York, where we planned to visit the Mather Homestead and

see a special exhibit of old samplers. Terry had developed an interest

in embroidery, and she was especially drawn to the handmade lines and

letters of samplers from the pre-industrial era—just as she had

been drawn to the lines and letters of the Hopper tombstones.

My intention all along was to photograph the samplers. We even stopped

for more film at Newberry's, in the Wellsville business district. But

when I attached my flash, I forgot to change the camera settings. That

turns out to be just one of several kinds of mistakes I tend to make.

As a result, my photographic efforts have an "emergent" quality: only

in situations where I feel fully comfortable do I have the concentration

needed for successful picture taking.

Thus my mistake at the museum was no accident. The newness of the place

fractured my concentration. Fortunately, however, my outdoor shots weren't

affected. For example, the one of the house with the double row of sugar

maples leading up to it came out fine:

As part of our tour we walked around the grounds and saw how the back

of the lot dropped off, into river bottom. But Wellsville wasn't just

a river town; it was also an old railroad town, located on one of the

country's earliest trunk lines. When completed in the mid-nineteenth century,

the Erie Railroad tied New York City to Lake Erie at Dunkirk, New York,

by traversing the upper reaches of several major watersheds: the Delaware,

the Susquehanna, the Genesee, and the Allegheny. For a short section it

actually followed the Genesee—from Wellsville to Belvidere, along

the route that Terry and I had driven earlier.

In leaving Wellsville, we again took the railroad route. But this time

we headed east, following Dyke Creek out of the Genesee watershed, along

Route 417 to Andover, New York. Past Andover, the railroad turned north

and soon reached its highest point—"an elevation of 1760 feet above

tide-water"18 —as it crossed into the Susquehanna watershed.

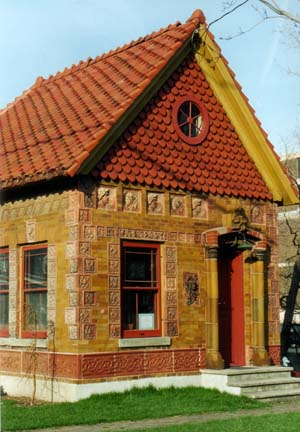

Our final stop of the day was at Alfred, New York. Driving into town,

I pointed out the many houses with terra cotta roofs. Grandma had been

interested in terra cotta, and on one of my visits with her she had asked

me to photograph the decorative tiles on the Surrogate's Building in Bath,

New York—one of the old brick office buildings that faces Pulteney

Square. It was Grandma who had told me about Alfred being a center of

terra cotta manufacture, a fact that I now shared wi th Terry.

When we arrived, a festival of some sort was under way, which made parking

a little difficult but which also gave the place a lively feel. We walked

around the campus of Alfred University and looked at some of the ceramics

exhibits. Then in town I showed Terry the former office of the Celadon

Terra Cotta Company:

Top to bottom it was covered with terra cotta, and in the rich light

of the late-afternoon sun it took on a magical appearance—like a

gingerbread house in a fairy tale. But we didn't linger, for the time

had come to return home: via Route 21 to Hornell, Route 36 to Dansville,

New York, and 1-390 the rest of the way.

Reaching Tom Territory

While Grandma was still living, New York's Southern Tier was for me the

world she described in her stories. On our drives together we sometimes

visited places where her stories were set. But I made no effort to map

the terrain. Instead, what I "mapped" were the stories themselves, taking

notes as she talked and writing them up more fully after returning to

Rochester.

Grandma's stories gave me such a powerful sense of place, that after

her death I wanted to explore the region on my own. At first I wasn't

sure how successful I'd be. Could I find all the family tombstones she

had mentioned? Could I locate the various farms, schoolhouses, and other

landmarks she had described?

As I drove the roads of the Southern Tier and gradually got my bearings,

I realized that the places in Grandma's stories weren't uniformly distributed.

There was a strong central axis—namely, the Conhocton-Chemung Valley—especially

from Bath to Corning. Moving away from that axis, the settings for her

stories became less dense, with some places figuring more prominently

than others: Elmira, more than Hornell; Watkins Glen, more than Dansville;

Keuka Lake, more than the Canisteo River; and so forth.

As that overall picture emerged, I began considering a new question.

In addition to locating the specific places Grandma had mentioned, I wondered

if I could delineate the area most richly tied to her stories.

Meanwhile, I began attending the monthly meetings of the Bath Area Writers

Group. At first I thought I'd make a project of compiling Grandma's stories.

Time after time, however, what I actually found myself preparing were

essays about my own interactions with the land. Although these essays

involved Grandma's stories, what unified them was my presence as a main

character.

In the process I began referring to the region I was exploring and writing

about as "Tom Territory." Starting with the confluence of the Conhocton

and Tioga Rivers at Painted Post, its boundary followed the Chemung to

Corning and Elmira. Then it turned north, following Route 17 (I-86) to

Horseheads, Route 14 to Watkins Glen, and Seneca Lake to Dresden.

Turning west at Dresden, the boundary followed Route 54 to Penn Yan and

Route 364 to the "y" with East Lake Road (several miles south of Canandaigua).

Next it headed southwest, following Canandaigua Lake to Naples and then

Route 21 through Wayland and on toward Hornell. Just outside Hornell,

it shifted to Route 36. The final stretch followed the Canisteo and Tioga

Rivers, from Hornell to Painted Post.

From the outset I had a pretty good idea why exploring Tom Territory

was important to me. It wasn't just because I wanted to continue my contact

with Grandma's stories—though that was certainly true. It was also

because I wanted to write in a way that was different from my RIT lectures

and my history of science research. Thus after taking my first essay to

the writers group, I told an RIT colleague that I was developing a new

voice for myself—one that needed the distance to Bath to feel comfortable

emerging.

The desire to become a writer wasn't wholly unprecedented. At various

times it had welled up within me as a clearly defined urge. While in first

grade, for example, I remember making up my own travel-adventure stories.

Further instances came late in high school and early in college, when

I prepared short compositions for my English classes.

After graduating from Rhodes College in 1974, I spent a year in Memphis,

working part-time and thinking through what kind of career I wanted. The

result was a decision to seek a master's degree in physics at Georgia

Tech, as the first step toward a Ph.D. in the history of science. But

also during that period the desire to write made another appearance. I

was reading books by and about Ernest Hemingway, and I found myself attracted

to his distinctive style. Again I did some writing. But this time it turned

out to be self-reflective, about the process of writing

"I need to write," I said, on sheets I still have in my files, dated

10 August 1975. "This need is based directly on my need to express myself."

Then in two and a half pages of single-spaced prose I surveyed where my

writing efforts stood. Along the way, I captured the basic "logic" that

still characterizes my identity as a writer:

My writing functions as a channel to my thinking. In some ways

it is my thinking. . . . Here, then, I can mention some of the conditions

which must be met for me to do both . . . . I must have lots of time to

myself. Time to get the urge to cover ground out of my system . . . .

Time to get the urge to organize out of my system . . . . And then still

more time to write down what I feel compelled to write down . . . . And

still [I must] have time left over with nowhere to turn. Time which can't

be filled by just letting my urges and compulsions loose. Time which must

be filled—if it is to be filled at all—by the creation of

some [new] thought. . . . Maybe someday the conditions for my writing

will change. But for the present it is a very fragile state of mind which

must be jealously and relentlessly . . . nurtured, encouraged, [and] fed.

For years afterwards the desire to write tended to remain underground.

But in the late 1980s it repeatedly surfaced, always briefly and usually

in August—when I was as far away from my regular teaching schedule

as it was possible to get, in the course of the academic year.

What happened after Grandma's death is that I decided to use the space

in my life I had once devoted to her to becoming a writer. That's why

I joined the Bath Area Writers Group—rather than, say, the Steuben

County Historical Society. Although writers and historians alike create

stories, when the chips are down historians have to get the facts right,

while writers have to get the words right. My doctorate was historical,

and I was teaching history courses at RIT. If I wanted to become a writer,

I needed to do something different. I needed to be around people who session

after session focused on the words more than the facts.

As I've already mentioned, I also knew that the physical distance from

Rochester was important—which is why I never gravitated toward the

programs offered here by Writers and Books. Basically I agreed with Leo

Szilard, the Hungarian-American physicist who is probably best known for

having convinced Einstein, in 1939, to sign a letter to President Roosevelt,

urging Roosevelt to consider the implications of nuclear fission research.

Toward the end of the war, Szilard composed a code of conduct for himself

that included the admonition:

Do your work for six years; but in the seventh, go into solitude

or among strangers, so that the recollection of your friends does not

hinder you from being what you have become.19

Grandma had died while I was taking my first sabbatical. But more to

the point, every meeting of the Bath Area Writers Group was a mini-sabbatical,

enabling me to become what I couldn't if I stayed at home.

With all that in mind, the significance of my Genesee vignettes emerged

more clearly. Until beginning the series, I had deliberately not written

about Rochester—at least, not in any systematic way. In order to

develop as a writer, my essays needed to be set and presented elsewhere—in

Tom Territory. Finally, however, I became comfortable enough with my new

identity to take as my subject the place where I actually live.

At first I intended my Genesee vignettes as an exercise that would go

no further upstream than the Mount Morris Dam. But having embarked on

the journey, I found it difficult to stop—and now I see why. To

stop at the dam would have been to stop well short of Tom Territory.

Continuing the vignettes offered an opportunity to link the Rochester

area with Tom Territory. But continuing also meant shifting the emphasis

off my recent Rochester experiences. Alongside those experiences, I was

now writing about experiences from my childhood, from Grandma's youth,

and from family history going back even further. In other words, I was

including the kinds of things that characterized my essays about the Southern

Tier.

Toward the end of the previous vignette—that is, toward the end

of the trip with Terry in April 1994—I reached the boundary of Tom

Territory. After leaving Alfred, we took Route 21 to Hornell, where we

picked up Route 36. The short stretch where Routes 21 and 36 coincided

was part of the line. By pushing my writing upstream from Letchworth I

thus succeeded in tying the terrain of my Rochester writing directly to

the region I had been writing about in my other essays.

Illustrations supplied by the author.

Notes

8. Notes on Visit, 18 -19 Aug. 1988, pp. 12 - 13.

9. Jessie Howell Finch, The Ancestral Lines of

Chester Everts Howell, 1867 - 1949, of Elmira, New York, U.S.A.

(Elmira, NY: Howell Associates, 1965), p. 54.

10. New York in the Revolution as Colony and State,

Vol. 11 (Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Co., 1904), p. 65.

11. Collections of the New York Historical Society

for the Year 1891 (New York: New York Histrorical Society, 1892),

pp. 160 - 161.

12. Notes on Visit, 12 - 13 May 1989, pp. 20 - 21.

13. Marie B. Cornell to William C. Greene, Jr., 25

Nov. 1969.

14. Marie B. Cornell to William C. Greene, Jr., 6 Feb.

1970.

15. Marie B. Cornell to Mrs. Lewis S. Van Duzer, 24

Nov. 1974.

16. Marie B. Cornell to Mrs. Lawrence O. Kupilias,

21 June 1974. This comment was deleted in the copy sent.

17. On the land transactions and the farm, see Finch,

pp. 53 and 57. On the "public house," see John S. Minard,

Allegany County and Its People: A Centennial Memorial History of

Allegany County, New York (Alfred, NY: W. A. Ferguson, 1896), p.

679.

18. Harper's New York and Erie Rail-Road Guide

Book, (1851; reprinted in Astoria, NY: J. C. & A. L. Fawcett,

p. 164.

19. Leo Szilard, "Ten Commandments," in S.

R. Weart and G. W. Szilard, eds., Leo Szilard: His Version of the

Facts: Selected Recollections and Correspondence (Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press, 1978), p. vi ("commandment" no. 9).

|