|

Genesee Vignettes

Personal Reflections on the Genesee River

A series of eighteen essays by

VIII. Grandma Cornell at Letchworth

One of the main reasons I had accepted the RIT job offer was the proximity

it gave me to Grandma Cornell. On visits with her in Campbell, I enjoyed

listening to the stories she was always willing to tell. Most were set

in the Southern Tier. But a few involved Rochester.

Her eldest son—my Dad's older brother (and Aunt Dotty's first husband)—lived

in Rochester before moving to a house on Keuka Lake. I have fond memories

of visits with my cousins on the lake, but I don't have clear recollections

of earlier visits with them. Nevertheless—as Grandma reminded me—such

visits had taken place, so that my relationship with the Genesee Valley

involved more than just the experiences I've accumulated since my arrival

in 1982.

Contact with Grandma also showed me another kind of "Genesee vignette"

I could write. In addition to my childhood visits to the area, there were

her personal experiences—which now came to me through her stories.

For example, as a schoolteacher she had attended occasional teachers'

meetings in Rochester and had spent some of her free time shopping at

Sibley's downtown.

Grandma's relationship to the Rochester area turned out to be complex.

Usually I'd visit her at her home. But there were times when Dad brought

her to visit me. On one such occasion—in 1984—we spent an

afternoon at the Genesee Country Museum, near Mumford, New York. The high

point for Grandma was a tour of the Hamilton House, which had once stood

on Main Street in Campbell:

After another visit—in 1985—I took Grandma home via Geneseo,

New York. She had often told me about her experiences during the years

1913-1915, when she attended the state normal school—now SUNY Geneseo.

Her experiences had included walks to the falls of Fall Brook. But what

we made a point of locating on our trip together was "the Bolt Club,"

the house on Main Street where she had roomed.

I don't recall ever going to Letchworth with Grandma. Nor do I recall

ever hearing her talk about the park. But later I realized it's a place

she had visited long before I was born. During her college years she had

taken pictures using a Brownie camera—a direct descendent of the

cameras by which George Eastman had democratized the making of images.

Many of the pictures we had gone through together were Brownie snapshots.

After her death, several more surfaced—one of which showed her sitting

on a grassy hillside, holding a Brownie camera in her lap:

Also included in the new batch were two taken at Letchworth. Neither

was labeled. But in one of them Grandma was standing between two women

on a rock ledge below the Lower Falls, with the photographer looking downstream:

In the other, Grandma was seated:

She also appeared in better focus and happier countenance. A comparison

of the clothing shows that the woman with her head bowed in the second

shot is the same as the one to Grandma's left in the first, which confirms

that the two pictures were taken on the same outing—an outing that

clearly included a stop at Letchworth.

IX. A Geological Orientation

In composing these vignettes I've found myself tending to cultivate a

geological orientation. Especially useful for this purpose have been the

popular writings of Bradford B. Van Diver and Thomas X. Grasso.2

But the source I now want to use is a more technical article, by a quartet

of authors, entitled "Morphogenesis of the Genesee Valley."3

If you examine a map of New York State, one of the Genesee's most prominent

features is a shift in its overall direction. Its upper reaches—from

its source in Pennsylvania to a point between Caneadea and Houghton, New

York—flow basically northwest, in parallel with the southeastward-flowing

Canisteo and Conhocton Rivers to the east. By contrast, the Genesee's

lower reaches flow northeast. The suggestion is that the current

watershed has been created out of what were once separate watersheds.

Or—in the geo-speak of the article:

Far from being an ideal valley system, an integral geomorphic

unit produced primarily by fluvial processes, the Genesee Valley involves

reaches with diverse origins and dissimilar histories.4

In surveying the twists and turns of my life, I've realized that it includes

a similar shift. Early in my senior year of high school I decided I needed

more time for my studies—especially for my physics class—so

I quit my part-time job at the Starkville Public Library and resigned

as president of my Explorer Post. More than the summer job I took after

graduating (as a junior counselor at one of the Fresh Air Fund camps near

Fishkill, New York) and more than my subsequent departure for Rhodes College,

the changes I made during the latter part of 1969 marked the real turning

point. Since then my life has flowed through a different watershed, one

that's defined by a distinctive kind of discipline—without which

I wouldn't have been able to choose a college major, attend graduate school,

or hold down a college teaching job.

Where the angular shift in the literal river occurs between Caneadea

and Houghton, the shift in the figurative river of my life resonates somehow

with the Mount Morris Dam. I had long noted that the dam is as old as

I am: it became operational at about the same time I was born, in late

1951. But more to the point is a functional likeness. Under normal circumstances,

something flows within me unimpeded, like the river under the dam. At

such times, my personality is tinted by colors from a spectrum of traits

that includes "honesty" and "naivete." But under conditions of stress,

the discipline I've cultivated since high school holds something back,

thereby imparting to my personality qualities from a different spectrum,

one that includes "up-tight brittleness" and "sullen mulishness."

Soon after that thought came to me, I went for another look. I was hoping

that a literal trip to the literal dam would clarify what the figurative

dam held back. But beyond the chain-link fence, all I could see was a

vast open space—defined below by the serpentine curves of the river,

above by soaring turkey buzzards, and across by the eroded strata of the

canyon walls:

A literal visit, I concluded, wouldn't get the job done. There was no

way to avoid the figurative journey of writing about my Genesee memories.

For the downstream vignettes, the selection of events hadn't been a problem—which

surprised me somewhat, since my earliest local history writing had focused

on the Southern Tier. But writing about Letchworth was proving more difficult

than I had expected. Although I was making progress, I was uneasy with

the way I had chosen to move upstream from the dam: instead of confining

myself to recent events, I had shifted to events from my childhood and

from Grandma's youth.

As this line of thinking unfolded, I was reminded of a dream that dated

back to May 1990. Grandma had died in January, and for several weeks thereafter

I had lived in her house, putting her papers into boxes and generally

straightening the place up. Later still I had helped my parents take a

load of furniture home to Mississippi, and on the way back I had visited

Terry in Knoxville. Only after all that had I resumed "life as usual"

in my Rochester apartment—which is when the dream came:

I was driving along a country lane, lined with trees on either

side. At the end of the road and to the right I saw a roiling wall of

water, ten feet high and maybe thirty feet across. It was churning and

frothing, yet staying in place. I realized that the water level was much

higher than the surrounding countryside and was threatening to break through.

As quickly as I could, I turned around and drove back the way I had come.5

Right away I suspected that the roiling wall of water symbolized strong

emotions, so now—in the context of my Genesee vignettes—I

could guess what lay behind the figurative dam. Like the actual Mount

Morris Dam, the discipline I had cultivated since high school allowed

emotions of the usual sort to flow unimpeded. But whenever strong emotions

threatened, those floodwaters got held back—until they could be

safely released.

So far, so good. But could I pin down the specific emotions the wall

of water represented? In part, I suspected, I was threatened by grief.

But only in part. Grandma had lived a full life, and the two of us had

spent considerable time together. I missed her; I'll always miss her.

Yet through continued contact with people who knew her—family members

and non-family members alike—I still sensed her presence. Thus the

dream had to involve something else, as well.

Another unsettling feature of the dream image was the absence of a dam.

Strong emotions were indeed being held back, but not by any visible restraints.

What aspect of my life was like that? Here the essential clue turned out

to be the dimensions of the roiling wall. After returning to Rochester

in April 1990, I had purchased and assembled four sets of metal utility

shelves, on which I put Grandma's papers—sixty boxes' worth. Two

sets stood in my dining room and two in my bedroom. But the combined dimensions

were almost exactly those of the water in my dream:

Already I had been thinking of Grandma's papers in riverine terms. Her

interest in family history and local history meant that as she aged, historical

material flowed to her from many different sources, and because she lived

alone in a fairly large house—with a sturdy barn out back—she

possessed ample storage space.

Behind that dam the material pooled up, year after year. So deep did

the impounded waters become that Grandma was reluctant to allow anyone

but close family members into her house. On one of my visits, while she

was napping, I snapped a strictly unauthorized photo of her kitchen:

Except for the sink, for her chair seat, and for the front half of the

stove top (note the light-blue burner covers I had gotten her, to minimize

the danger of fire), virtually every horizontal surface was stacked with

papers. Such views were exactly what Grandma hadn't wanted others to see—and

if she had found out about my picture, I'd have been in hot water!

Like the kitchen, the other rooms of her house were filled with papers.

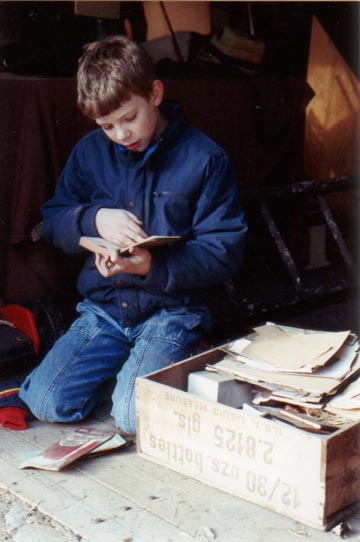

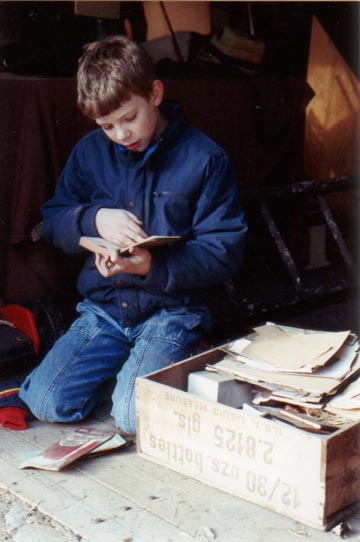

The same was true of the barn—where even a brief tour after Grandma's

death turned up material that interested my brother Don's eldest son,

Steven:

But Grandma's death represented a major dam break. In the months that

followed, her house and barn were sold and their contents distributed.

Fortunately, I was in the middle of a sabbatical at RIT and thus had

the time needed to create a new dam. The physical artifacts—furniture,

clothing, books, and so forth—were beyond me. Like the Genesee floodwaters

referred to in the title of Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck's book, the physical

artifacts were "runnin' crazy."6 They rushed by so fast I scarcely

noticed where they ended up. But because I wanted to use them for family

and local history projects, I was determined to keep the papers together.

Proceeding one handful at a time, I'd use a portable vacuum cleaner to

remove the dust. Then I'd put the dusted handful into a file folder and

put the folder into a box. When the box was full, I'd take it upstairs

and add it to the growing stack in one of the bedrooms. In early March,

Uncle John (Dad's younger brother) and I loaded all the boxes onto his

pickup and drove them to Aunt Dotty's, for temporary storage. Then after

my return to Rochester I rented a van and brought them to my apartment.

In effect, what I had done was to create an archival collection like

the ones I had used in the Library of Congress and elsewhere for my history

of science research. Until then my work with such sources had been emotionally

low-keyed. But my dream served as a powerful notice that the archival

boxes I saw each night when I turned in were actually quite different

from the archival boxes I was accustomed to using. Yes, I had created

a new dam; Grandma's papers were now held back by a sturdy arrangement

of file folders, archival boxes, and metal shelves. Yet I wasn't free

to treat that material in an emotionally neutral way. Behind the silent

rows of gray and brown boxes lay the churning and frothing I had seen

in my dream.

Compounding my uneasiness was the limited extent of my previous local

history writing. While Grandma was living, I kept such work to a minimum;

my visits with her came first. Along the way, I sensed the richness of

the material. But not until after processing her papers, did I see the

full extent of the task I had undertaken—and its vastness terrified

me.

Only now am I feeling comfortable enough to reflect on all this, and

the main reason is my regular participation in the Bath Area Writers Group.

After Grandma's death, I began writing short essays for presentation at

their monthly meetings, and from time to time I've revised my essays for

publication in The Crooked Lake Review. Slowly the rising volume

of finished work has taken the edge off my fears—and given me a

new perspective on my 1990 dream.

Here, finally, the geology article about the Genesee assumes its full

importance. "Fluvial modification," the authors noted, "though geologically

dominant at present has only begun to produce in the Genesee Valley the

geomorphic coherence toward which undisturbed hydrologic basins evolve."7

Or—to translate their geo-speak—the changes being wrought

by the river today have only begun transforming the separate watersheds

of past eras into a single, coherent system.

Apparently I don't live in a world that allows me to develop, from birth

to death, as an entirely new river. My life isn't emerging as an "undisturbed

hydrologic basin." Yet the kind of writing I'm doing in these essays turns

out to be a process of "fluvial modification" that's slowly imparting

"geomorphic coherence" to my life. Or—to return to the passage quoted

earlier—the "fluvial processes" of my writing are slowly creating

"an integral geomorphic unit" out of what previously had been separate

watersheds.

Whether I find myself in the terrain defined by my disciplined academic

work, or in the terrain defined by my childhood interests and experiences,

or in the terrain defined by Grandma's past—no matter what the terrain—I

now understand that integration, coherence, and unity will, in fact, come.

Through my writing I'll be able to make the various fragments whole. In

that sense, I now see that my 1990 dream offered as much a promise as

a threat.

Illustrations supplied by the author.

Notes

2. Bradford B.. Van

Diver, Roadside Geology of New York (Missoula, MT: Mountain

Press, 1985); and Thomas X. Grasso, "Geology and Industrial History

of the Rochester Gorge," Rochester History, Vol. 54, No. 4

(Fall 1992), pp. 3-43; and Vol. 55, No. 1 (Winter 1993), pp. 3-35.

3. Ernest H. Muller, Duane D. Braun, Richard

A. Young, and Michael P. Wilson, "Morphogenesis of the Genesee Valley,"

Northeastern Geology, Vol. 10 (1988), pp. 112-133.

4. Muller, et al., p. 112.

5. Paraphrase of Dream Notes for 26 May 1990.

6. Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck (with Edward

P. Curtis, Jr.), Runnin' Crazy: A Portrait of the Genesee River

(Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co., 1996).

7. Muller et al., p. 112.

|