|

Genesee Vignettes

Personal Reflections on the Genesee River

A series of eighteen essays by

I. Introduction

II. The Mouth of the Genesee

III. The High Falls

I. Introduction

Although I lived in several places during my youth, I did most of my

growing up in Starkville, Mississippi, a small town that was, nevertheless,

the largest in Oktibbeha County—making it the county's main business

and entertainment center. Starkville was also the county seat, and just

down the hill from the courthouse was the jail that Johnny Cash sang about

on his San Quentin album. Another distinctive feature was the presence

a couple miles away of Mississippi State University, which had a student

population nearly as big as the town's. Football games—especially

with arch rival "Ole Miss"—were important campus activities, and

I well remember the clangorous din of students ringing their cowbells

each time MSU scored a touchdown.

It was Mississippi State that brought us to Starkville. In 1961 Dad accepted

an appointment as a full professor in the Chemical Engineering Department,

and for nearly a decade thereafter campus experiences came to me without

my giving them much thought: Sunday dinners in the cafeteria, movies at

the student union, occasional visits to Dad's office, even a summer course

after my junior year of high school. But when I matriculated, I chose

to go elsewhere.

I didn't realize that in leaving home for college I'd be leaving home

for good. Nor did I realize that I'd be exchanging small-town life for

life in one city after another. With each move, I'd have new schoolwork

uppermost on my mind. In Memphis I was an undergraduate, and in Atlanta

I worked on a master's degree. I went to Baltimore for my Ph.D. And I

began my career as a college teacher in Rochester. Yet I wasn't oblivious

to my surroundings. In Memphis, for example, I remember joining some of

my friends for a spur-of-the-moment drive downtown to watch the sun set—with

the bluff above the Mississippi giving us a panoramic view of the Arkansas

delta. In Atlanta, I remember riding my bicycle each morning to the Georgia

Tech campus: for several blocks I'd labor uphill; then after crossing

Peachtree Street I'd coast most of the rest of the way. As for Baltimore,

I remember my first visit, when the view from the train showed me the

rise and fall of the land in the rise and fall of block after block of

two-story row houses.

More than I realized, I soaked up the ambience of city life—so

that each time I returned home, I'd find the contrast quite striking.

In a city I could spend an entire day downtown without seeing anyone I

knew—and if I did, the occasion was noteworthy. Back in Starkville,

however, I could scarcely enter a store or walk half a block along Main

Street without seeing several familiar faces. Throughout my college years

I found myself uncomfortable with both situations—the massive anonymity

of each city versus the unrelenting familiarity of my hometown. But as

long as I kept moving, the issue never got resolved—because I never

stayed in one place long enough to feel like I truly belonged.

What changed all that was living in Rochester far longer than anywhere

else. I hadn't intended to stay. The original idea was to acquire some

teaching experience while finishing my dissertation and then to move on—probably

to a university in some other city. As a result, my earliest Rochester

experiences were just as fragmentary as my experiences in Memphis, Atlanta,

and Baltimore.

But because I've lived in Rochester so long, I've gradually realized

that my city memories from all these places are like the fossils I happen

to find in creek beds or road cuts. Although I keep my eyes out for them,

I don't collect them systematically. Instead, they come to me as isolated

events or unplanned experiences. But the fact that they appear where they

do turns out not to be accidental. Different layers of rock contain different

fossils—or none at all. Thus the presence of particular fossils

testifies to the presence of particular strata.

Similarly, my memorable city experiences—however fragmentary—testify

to the presence of vast layers of collective experience. I suspect that

more than the built structures (the houses, the office buildings, the

roads, and so forth), it's the presence of these distinctive layers of

collective experience that gives any city its overall character.

Just as no one type of fossil—or no one layer of rock—serves

to define fully an entire geological region, so any city's identity is

necessarily complex. But rather than dealing with Rochester's full complexity,

all at once, my approach was to start with a particular theme. Upon reflection,

what most struck me about my earliest Rochester experiences was how many

of them involved the Genesee River. Thus the central premise for the essays

emerged: I'd attach each memory to its appropriate place along the river

and then proceed in topographical order, upstream, from one vignette to

the next.

Meanwhile I planned to keep in mind a pair of questions: why had I come

to Rochester and why had I stayed? By tracing my memories along the Genesee

I hoped to discover what it was about the place that had attracted and

kept me here. Initially I expected to write just a handful of essays,

focusing on my recent experiences in or near Rochester. But for deeper

answers to the questions I had raised, I found myself writing more and

more, going further and further upstream each time, until I had reached

not only the headwater of the river but also the headwaters of my intellectual

identity.

II. The Mouth of the Genesee

Although I can't remember the first time I visited the mouth of the Genesee,

fairly early after moving to Rochester I'm sure I followed Lake Avenue

northward, to Lake Ontario. I have no recollection of the public beach,

which is located just west of where the river flows into the lake. Nevertheless,

the trip stands out because of the Kodak buildings I passed along the

way. I had always linked Rochester with Kodak. But only after seeing for

myself the colossal scale of the facilities at Kodak Park did the company's

status as a global giant really sink in.

In preparing to write about my earliest Rochester experiences, I was

able to draw on more than just my memories. Also helpful were my files.

For example, my "Rochester" folder included a clipping from the Democrat

and Chronicle for Friday 13 July, 1984, and my daily notes reminded

me that I was at the time immersed in the work on my dissertation—and

very much in need of a break. The newspaper account of some twenty tall

ships arriving to celebrate the city's 150th anniversary fascinated me—so

much so that I took Saturday off: I got a ticket to the Harbor Festival

and rode there on one of the special shuttle buses. Exploring the ships

turned out not to be possible. The crowds were so large that the tours

had to be canceled. But I do recall walking to the old stone lighthouse,

located on high ground, well inland from the lake shore.

In June 1993 I finally did get a chance to tour a tall ship, when Dad

came to Rochester on his way to his annual high-school alumni dinner in

Campbell, New York. As an afternoon excursion, we decided to drive to

the mouth of the Genesee and attend the Harbor Festival—where one

of the main attractions was a full-scale replica of the Niña,

which had been built to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Columbus's

first voyage to the New World.

It wasn't Columbus who had developed sailing ships capable of navigating

unfamiliar waters, over great distances, and then returning home safely.

Instead, that honor belongs to the Portuguese. In the early fifteenth

century they had begun exploring the west coast of Africa, and as their

voyages extended further and further from home, they found it necessary

to make changes in their ship designs and sailing practices—so that

by the end of the century they had developed a new technological system,

as well as an overseas route to India.

What Columbus did was to adopt the Portuguese system (the Niña

was a Portuguese-style caravel) but then apply it toward a different aim:

reaching the Far East by sailing west. As a result, his first voyage revealed

not so much the existence of a new continent—for he went to his

grave still believing that he had reached the Far East. Instead, his voyage

revealed how Europeans had by then created a highly effective oceanic

means for achieving their larger ends. Using sailing ships they were able

to extend the power of their nation-states, gain wealth through global

trade, convert foreigners to Christianity, and learn far more about the

world than had been known by the ancient Greeks and Romans.

Now I had an opportunity to see for myself a replica of one of the early

discovery ships. On board, I could feel how solid the construction was.

The thick planks under my feet represented a huge amount of wood, and

everywhere I went I could smell the pitch used to make the joints watertight.

Also striking was the absence of straight lines. Curved upper surfaces

kept water from collecting, while curved sides provided the overall shape

needed for smooth forward motion and for balancing the wood's internal

strength against the pressure of the water.

We stayed that evening until the Niña departed. How eerie

it was to watch her glide toward the lake, escorted by a modern fireboat

and illuminated on one side by the carnival lights. Despite her importance

in world history, she seemed so small. On the tour I hadn't been able

to take more than a few steps in any one direction, and the whole vessel

had bobbed in the wake of each passing pleasure boat. Now as I watched

her recede into the fading twilight, I wasn't sure I'd want to be aboard

her during a storm on the lake—much less one on the high seas.

III. The High Falls

If memory serves me, I first visited the High Falls downtown in March

1983, toward the end of my first year at RIT. My history colleague, Richard

Lunt, had invited me to lunch at the Lost and Found Tavern (later the

Phoenix Mill Publick House and, most recently, Jimmy Mac's Bar & Grill)—in

an old brick building near the edge of the gorge. I have no recollection

of the falls themselves. Instead, what I remember is our mealtime conversation

about Dick's latest research project.

Dick always had a project he was working on—if not a research project,

then something related to his courses. When I interviewed for the RIT

job, he was the one who asked me what new courses I wanted to teach. Although

I designed only one completely new course before he retired, during that

same time span, he designed two and also redesigned a third. As a result,

he succeeded far better than I at keeping his research in synch with his

course work—so that, for him, research and teaching were never wholly

separate activities.

At any rate, after lunch we must have walked on the pedestrian bridge

that spans the gorge, because when my parents came a year later (in May

1984), I knew it would be a good place to take them.

Since then, I've been back to the High Falls many times—with Thanksgiving

1986 being one especially notable example. That year Mom and Dad joined

me for Thanksgiving dinner. The next day my brother Bill, his wife Linda,

and their daughter Anna came for an overnight stay, and as an outing we

all went to the High Falls. Finally, on Saturday we drove to the Holiday

Inn in Gang Mills, New York (near Painted Post), where we met other family

members to celebrate the 90th birthday of my grandmother, Marie B. Cornell.

More recently my visits to the High Falls have included the museum in

the Browns Race historic district. Those exhibits, when coupled with the

views from the pedestrian bridge, offer an excellent way of showing out-of-town

visitors why Rochester is located where it is—namely, to utilize

the power of the falls. Many of the early mills were grist mills that

ground locally-grown wheat into flour. But all along, Rochester's water

power was used for a variety of industrial operations—often on a

massive scale, as attested by the reconstructed waterwheel at the Triphammer

Forge site.

Also at the museum is a short video showing how the falls were formed

as the ice retreated at the end of the last Ice Age. When I first moved

to Rochester, I was surprised by the flatness of the terrain. Since then

I've learned that the explanation has several facets. The region is flat

because vast quantities of relatively soft rock have been removed through

erosion. The ice sheets of the Ice Ages also left their mark, scouring

the terrain in some places and leaving massive deposits elsewhere. Finally,

as the ice retreated the region became the bed for a sequence of lakes,

each at a lower level.

Generally speaking, the ground around Rochester rises slowly but steadily,

north to south. Lakes formed because water got caught between the ice

to the north and the high ground to the south. As the ice retreated, new

outlets for these lakes were uncovered, allowing them to fall to lower

and lower levels. In the process the Genesee also had to fall further

and further. Whenever it flowed across crumbling shale, it quickly cut

a deep channel for itself. From time to time, however, it hit resistant

limestone or sandstone—which is what produced the waterfalls. Thus

the High Falls turn out to be just one in a series. Further downstream

are two others. The video at the museum showed how these falls first emerged,

close to the lake, and then how they moved steadily inland, due to on-going

river erosion.

Of course, only after the full retreat of the ice and the lowering of

the lake to its current level could the terrain become tree-covered. The

resulting woodlands were actively managed by the Iroquois—notably,

through their hunting and agricultural practices, through their network

of trails, and through the periodic relocation of their villages. But

their approach left intact the overall contours of the forest. Not until

the arrival of European-American settlers was the appearance of the region

transformed wholesale.

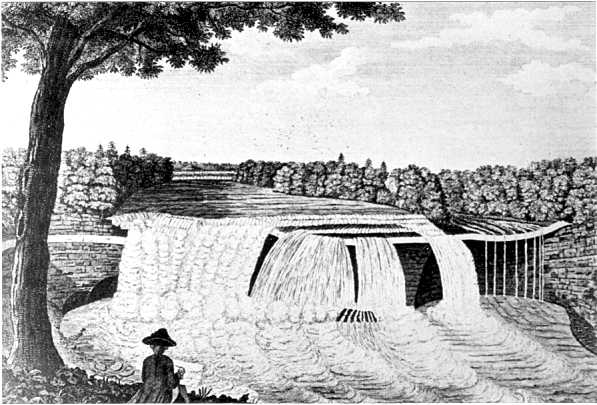

So completely has the High Falls area been transformed by modern development,

that when I first came across a mid-eighteenth-century sketch—made

by a British officer during the French and Indian War—I was dumbstruck.

As viewed from the pedestrian bridge today, the falls are surrounded by

buildings. But in Thomas Davies's sketch the horizon is defined by treetops,

uninterrupted except by the river itself:

The engraving is one of a set of six from the region—see Edward

R. Forman, "Casconchiagon: The Genesee River," Rochester Historical Society,

Publication Fund Series, Vol. 5, (1926), pp. 141-145.

Illustration supplied by author.

|