|

Genesee Vignettes

Personal Reflections on the Genesee River

A series of eighteen essays by

XVII. A Triple Divide

I had long known that the Middle Branch of the Genesee above Gold, Pennsylvania,

leads to a triple divide, a hill down which rain and melting snow flow

into three very different watersheds.

To the north the water flows via the Genesee, Lake Ontario, and the Saint

Lawrence into the North Atlantic. To the southeast it flows via the West

Branch of the Susquehanna and the Susquehanna proper into the Chesapeake

Bay. Finally, to the southwest it flows via the Allegheny, the Ohio, and

the Mississippi into the Gulf of Mexico.

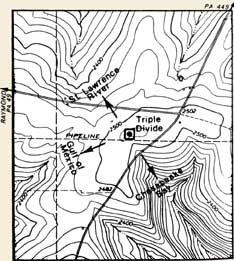

Although I had previously located the triple divide on a USGS topo map,

I hadn't been sure about the feasibility of visiting it until I came across

a book entitled Outstanding Scenic Geological Features of Pennsvlvania.66

From the entry on the triple divide I realized that even if the land was

posted, we'd at least be able to see the divide from the road—and

we could drive there by following the map the book provided.

New growth was just starting to appear in the woods when Terry and I

made the trip in early May 1999. Our route took us to the point where

I had stopped in December. But this time we kept going: past the farm

I had seen near the crest, past the turnoff to Raymond, Pennsylvania,

and past the summit. We then parked and began walking back the way we

had come:

Earlier in the morning there had been rain showers, and still the sky

was filled with clouds. But now the sun was occasionally breaking through,

so we didn't need rain gear—-just hiking boots for the mud. Because

of where we'd parked, we were on the Susquehanna side of the divide. To

our right the land quickly dropped away, into the valley for Pine Creek,

which joins the West Branch of the Susquehanna at Jersey Shore, Pennsylvania.

Further on, near the hilltop itself, there wasn't much to see. Markers

for a natural gas pipeline crossed the road and cut through the field

to our left, just south of where our map located the divide.

Here we found no long-distance views (which would have been toward the

Allegheny watershed). Instead, what we saw was an irregular line of trees

along the far edge of the field.

As the road crested, however, there opened before us an unexpectedly

broad view of the Genesee watershed. Beyond the turnoff and the farm we

had passed earlier, we glimpsed in the distance the shallow valley of

the East Branch:

Further to the left was the break in the hills through which the Middle

Branch made its southward run. Although it didn't photograph well, it

fascinated me—for it was clearly an ice-shaped gap.

In my travels around Western New York I had seen numerous instances of

ice-shaped terrain. Now I could confirm that the uppermost reaches of

the Genesee watershed had likewise been reshaped during the Ice Age. But

from my reading I also knew that the most recent ice sheet had stopped

its southward advance not far from where our car was parked.

In his 1956 USGS study of Potter County, Charles S. Denny noted that

the ice had left behind characteristic rock deposits. Although emphasizing

a technical account of this "glacial drift," the study also included a

powerful verbal image:

The drift border is relatively straight and crosses [the county

diagonally] with little regard for the major topographical features, thus

suggesting that the Wisconsin ice sheet had a relatively straight and

steep front.67

The direct evidence for the ice front wasn't obvious to me. But with

Denny's image in mind I realized we hadn't just parked in a different

watershed. For the first time in our Genesee travels we had moved beyond

the influence of the ice.

Originally I hoped to explore some of the sites Denny had mentioned,

but along the way I lost my concentration. In large measure that came

from waiting too long to eat lunch. The day's cool temperatures were perfect

for hiking but not for our planned picnic at the triple divide. Although

we tried driving in search of an alternative spot, I didn't know the area

well enough. Finally, Terry suggested that we eat our sandwiches in the

car—which is what we ended up doing.

But now I see that my concentration also broke because I wasn't sure

how to handle the shift in my thinking. I had returned to Potter County

fully expecting the triple divide to provide the basis for concluding

my vignettes. Although the divide was indeed a feature of the landscape

that we could comfortably explore on a day trip, what grabbed my attention

turned out to be something whose dimensions were much more extensive.

At first I tried keeping the idea of the ancient ice front strictly localized.

In the absence of obvious direct evidence, I imagined the line being marked

with metal plaques, like the furthest advance of an army across a Civil

War battlefield. But then another image surfaced. Maybe our experience

was more like a beach trip, so that Terry and I had walked along the former

"shore" of an elevated "ocean" of ice at its moment of "high tide."

At the time of the region's first European-American settlements, the

existence of this vast ocean of ice had been completely unknown. Not until

the 1840s had scientists realized that much of the world was once covered

by continental glaciers, and not until after the Civil War had the line

of furthest advance into Pennsylvania been systematically mapped.

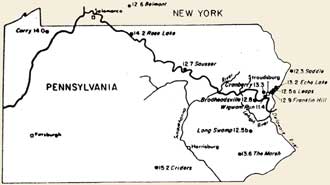

In a 1980 publication by the state's geological survey I came across

an updated version of that line68:

The late Wisconsinan glacial boundary in Pennsylvania and New York and

sites of radiocarbon dates to the nearest 0.1 thousand years (13.2 = 13,200

years ago).

The New York boundary is drawn after Muller (1977) and the northwestern

Pennsylvania

boundary is drawn after White and others (1969). The boundary throughout

is

approximately that mapped by Lewis and Wright (Lewis, 1884).

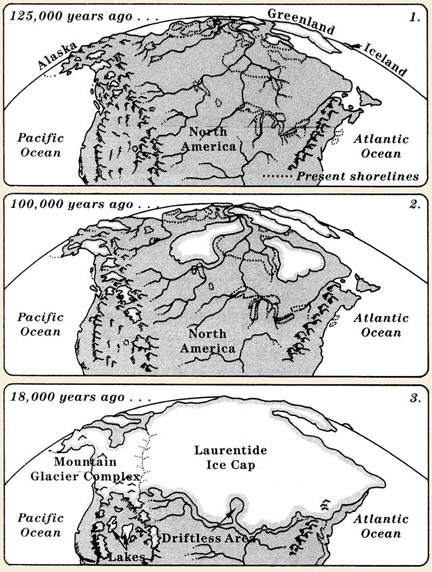

Of course, the Pennsylvania map traced only a limited portion. As shown

in a series of illustrations from Written in Stone: A Geological History

of the Northeastern United States,69 the ice front actually

stretched from the unfrozen Atlantic to the unfrozen Pacific.

The advance of the Laurentide ice cap reached its greatest extent about

18,000 years ago.

Sea levels were lower because large amounts of water were frozen.

Gone, then, was the modest scale of the triple divide. Gone also was

the prospect of a quick conclusion. Instead, I was left with the disconcerting

challenge of writing about one of the earth's most extensive surface features.

As a way of getting some traction here, I returned to the underlying

goal of my project. While following the Genesee River upstream, I was

reflecting on why I had come to Rochester and why I had stayed. Already

I knew several important answers. I had come because of my job at RIT

and the proximity it gave me to Grandma Cornell; I had stayed because

of Terry's willingness to move from Knoxville and because of my comfort

with Rochester's size (as a relatively small city) and the local climate

(with four well-defined seasons). The project itself, however, was bringing

to the surface yet another answer. As I explored the countryside, I was

finding that some of its physical features resonated with my inner sense

of self.

Based on what I knew about the teachings of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung,

this role of the landscape was unexpected. Freud viewed the human psyche

as being structured by complexes that originated in early childhood, on

the basis of how an infant related to its parents. For his part, Jung

viewed the human psyche as being structured by different unconscious personalities

(Anima or Animus Figures, Shadow Figures, etc.) that related to the Ego

(the Conscious Self) in various ways.

Of the two approaches, I tended to find Jung's more useful. The events

and circumstances of early childhood seemed too far removed from adult

realities. Instead of trying to conjure up my earliest experiences, it

made more sense to try bringing the various personalities of my psyche

into better relationship.

To express this distinction I drew an analogy with the early nineteenth-century

debate over how best to explain the earth's geological features. According

to the Catastrophists, the earth's mountains, canyons, etc., had been

shaped by special forces no longer at work (worldwide floods, worldwide

chains of volcanoes or earthquakes, etc.) and hadn't changed significantly

since then. By contrast, the Uniformitarians insisted that the only forces

at work in the past had been exactly like those we observe today (flooding

and sedimentation of the usual sort, volcanoes and earthquakes of the

usual sort, etc.).

My preference, then, was for Jung's "Uniformitarianism," rather than

Freud's "Catastrophism." But that very analogy exposed a lacuna in the

teachings of Freud and Jung. Both focused on relationships: Freud,

the relationship of an infant to its parents, and Jung, the relationships

between the Conscious Self and the component personalities of the Unconscious

Self. As valuable as all that was, my own psyche seemed to have structure

of an additional kind. My dreams, for example, often involved distinctive

terrains that I could map when I awoke. More to the point, however, my

travels in the Genesee watershed were facilitating the process of self

exploration. Time and again I was coming across topographical or geological

features that helped me better understand who I was.

Given the importance of geology to the exploration of my inner landscape,

I occasionally wondered if I had picked the right profession. As I thought

this idea through, however, I found I wasn't really tempted to treat the

earth's physical features as objects of scientific study. Instead, what

I found useful was the suggestive likeness between certain features of

the literal terrain and certain features of my psyche.

That was one way I began getting some traction. Another came when I recalled

that my early vignettes had analogized the river to the systematic creation

of new knowledge—that is, to research. In my history of science

projects I approached scientific research as a social phenomenon. Although

pursued by individuals with distinctive temperaments and life experiences,

scientific research was also a collective enterprise, profoundly shaped

by cultural expectations, social norms, and organizational policy.

In my vignettes, however, I thought I was doing something different.

I thought I was approaching research as a personal activity. Moving further

and further upstream was thus supposed to be moving me closer and closer

to my identity as a researcher.

The problem was that instead of reaching a uniquely personal point of

origin, I stumbled onto a massive ice front that had dramatically reshaped

much of the continent. No wonder I lost my concentration! Just when I

expected to uncover the ultimate terms of my individual identity, I found

my attention drawn to something so massive that its psychic equivalent

could possess meaning only in social terms.

Yet I really couldn't claim to be completely surprised. In taking a biographical

approach to the history of science, I had studied the social process by

which individuals develop their distinctive identities. What I hadn't

yet done, however, was to apply that approach to myself-at least, I hadn't

done so explicitly, as the featured theme of a particular essay.

Along these lines, the book that most influenced me was Erik H. Erikson's

classic account of Martin Luther.70 As people make the transition

from childhood to adulthood, most assume identities based on the options

offered them by their societies. The closeness of the fit may vary from

individual to individual, but most people find ways to rely on existing

conventions.

Occasionally, however, there appear individuals for whom the existing

conventions prove insufficient. Of these, a tiny number go on to devise

new conventions for themselves. In Luther's case, the new convention was

religious. But new conventions need not be restricted to religion. The

real point is that by inventing ways to meet their personal identity needs,

these individuals end up doing something profoundly social—because

the identities they create often become new conventions for others to

consider.

Even if most of us don't really invent identities for ourselves, the

effort to find something appropriate can still require considerable creative

energy. That was certainly true in my case. Although I had a religious

upbringing, the details of conventional religious practice hadn't "stuck"

very well. Likewise, I had been raised to respect "family values" but

hadn't married or had children of my own. From my point of view, I was

definitely middle class. But that wasn't an identity I felt comfortable

embracing, because in American society the formal adoption of a class

identity tends to be discouraged.

As I sorted through the various possibilities, however, the one that

most resonated with the transcontinental ice front turned out to be the

way in which society divides its labor. Every society has conventions

for who does what work. At the time that the literal ice front reached

the triple divide, all human societies were still in the hunter-gatherer

stage, with minimal social divisions of labor. Only as the ice receded

did people begin domesticating plants and animals, thereby creating for

themselves both settled agriculture and cities. With that transition came

a new division of labor, one that remained dominant until fairly recently.

From my study of colonial technology, I knew that European Americans

had established their settlements using a simplified version of the urban/agricultural

division of labor. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries most

colonists—perhaps upward of 75%—lived and worked on farms.

Whether male or female, black or white, young or old, rich or poor, most

made their living through agricultural pursuits. From the outset, of course,

there had been colonial cities. But these were mainly centers of trade,

with some craft production—such that 15-20% of white males were

merchants or artisans.

The emphasis on agriculture made colonial America seem quite foreign

to me. So too did the reliance on relatively unspecialized craft production.

Most striking of all, however, was the paucity of learned professionals.

Lawyers, medical doctors, ministers, etc., were present, but only in small

numbers. They didn't really comprise an occupational group; they didn't

register as a significant percentage in the social division of labor.

What changed all that was industrialization. As the structure of the

economy shifted toward manufacturing—first with the adoption of

a new style of production (using machines located in factories) and then

with a dramatic increase in the scale of production (the rise of Big Business)—there

emerged a new social division of labor. The traditional professions specialized,

and a host of new specialities emerged—including various kinds of

scientists and engineers. Practitioners of the new specialties sought

ties among themselves and became self-aware groups. To oversee their efforts

they established national professional societies, and to facilitate the

training of future practitioners they created specialized college curricula.

As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, members of my family

got caught up in that process. They began going to college, and some even

went on to graduate school. By the time I made the transition out of adolescence,

I took the new social division of labor for granted. My main challenge

was to choose a suitable professional specialty. Using standard categories

like "science" and "engineering" turned out to be more problematic than

I anticipated. But once I had gotten a taste of research, I was sure I

wanted to participate in the enterprise of new knowledge creation.

Only now, however, am I seeing how distinctive all this really is. The

knowledge produced in an industrialized world looks quite different from

the knowledge produced in a world dominated by farming and craftsmanship—which,

in turn, looks quite different from the knowledge produced in a world

of hunter-gatherers.

In short, my trip to the triple divide popped me out of my personal quest

and forced me to take a more detached look at the social enterprise of

which I was a part. Like an advancing ice sheet, thousands upon thousands

of specialists—supported by hundreds upon hundreds of institutions—have

been (and still are) scouring the landscape of human experience. Willy-nilly,

I was a contributer. I too was helping to reshape the contours of our

collective knowledge.

Yet even that realization didn't feel like a conclusion. Something

still remained missing. The trouble was, I had no idea what to try next—leaving

me little choice but to let the project sit for a while.

XVIII. Rose Lake

In exploring the Genesee watershed, I've also been exploring how I go

about knowing the world around me. The "I" of my essays is a truth seeker,

and my travels upstream have brought me into contact not just with the

river's various topographical features but also with various cognitive

structures inside me.

I say "inside me," yet I've learned that my ways of thinking aren't really

my own creations. I've indeed gone through the personal creative process

of assimilating them, but they've actually come into existence through

historical processes that predate my individual existence.

As I worked all this out, I realized there remained a feature of the

Genesee watershed that I still wanted to write about. In visiting the

triple divide, I had actually overshot the spring that the classic accounts

identified as the river's source. Superficially, the omission was based

on my reluctance to ask at the farmhouse for permission to walk on their

land. More profoundly, however, I sensed that my project included something

I didn't yet understand well enough to act on.

That "something," I learned from my reading, probably lay at the symbolic

level—with the river itself being the primary symbol. For example,

in Patterns in Comparative Religion the historian of religion

Mircea Eliade wrote:

Waters are the foundation of the whole world. . . . water symbolizes

the primal substance from which all forms come and to which they will

return . . . . . . . [water] precedes all forms and upholds

all creation.71

As a result, flowing water has special appeal: "it is 'living,' it moves;

it inspires, it heals, it prophesies."72

From that point of view, my exploration of the river assumed a spiritual

character—especially with regard to the river's headwater sources.

Involved here wasn't just my reluctance to ask for permission. Nor was

it really my lack of understanding of what the situation meant. Instead,

when I drove by the farm where the spring was located, I simply didn't

find the situation spiritually compelling. The site wasn't speaking to

me; I didn't feel moved to stop the car.

By contrast, stronger tugs were coming from a site I first learned about

from my library sources. Referring back to the previous essay, the map

that marked the furthest extent of the Wisconsinan glaciation in Pennsylvania

showed a tiny lake in the upper reaches of the Genesee watershed. The

earliest organic remains found there (pine, spruce, and birch pollen)

had been radiocarbon dated to 14,200 years ago. That made Rose Lake one

of the oldest surface features of today's Genesee watershed. That also

made it a place that intrigued me.

Thus the basic idea for my day trip in August 2002 was to visit Rose

Lake. Not knowing just how the experience would pan out, I also intended

to visit source sites on each of the river's three branches. Surely, I

thought, a visit to one of these would help me write about the oldest

cognitive structure I sensed inside me, namely, storytelling itself.

My awareness of storytelling as a cognitive structure had emerged in

response to my undergraduate studies. Although I was a science major,

I found my interest shifting from mathematical proofs and experimental

results to accounts of how and why people first obtained those proofs

and results. Acorns come from oak trees through a process that has no

dependency on human will. By contrast, mathematical proofs and experimental

results emerge only through a process of willful human behavior. As natural

as mathematical proofs and experimental results may seem to the researchers

who produce them, they are cultural achievements; their production can

always be cast as a story of human striving. It's such narratives (and

not the proofs or the results, in and of themselves) that fascinated me.

The trouble was that when I entered the history profession as a graduate

student in the late 1970s, traditional narrative presentations had fallen

somewhat out of fashion. In addition, political history had lost pride

of place to the New Social History, which emphasized groups and activities

long held at the margins of historical accounts: women and African Americans,

work practices and the routines of everyday life, and so forth.

Of course, those groups and activities are important. But when combined

with an emphasis on quantitative (especially statistical) methods, the

New Social History seemed to me more like historical sociology than anything

else. Because I had come to history with bachelor's and master's degrees

in physics, historical sociology held no appeal. Had I wanted to become

a scientist, I thought at the time, I would have chosen a field where

mathematics really was the natural language of the phenomena

being studied and where experimental methods really could be

employed.

My concerns surfaced in an essay I wrote in May 1979 at the end of my

second year as a history of science graduate student. To those who viewed

history as being a science, I formulated my response:

If history is a science. . . then I have made a grave error, since

I came to the history of science because I had rejected a career in

science. What is more, if history is [a] science, [then] it is certainly

a poor substitute for physics. If it is science you want . . . get

thee to a physics laboratory!73

In part, I was venting my frustrations. But more importantly I was trying

to express a change in my thinking. That year I was serving as the department's

teaching assistant for the undergraduate survey course. In talking with

Russell McCormmach, the instructor during the second semester, I voiced

my larger concerns. His response was to suggest that I read an essay by

the American historian David Hackett Fischer.

In his essay Fischer argued that history is neither purely scientific

nor purely literary; instead it involves both, in a "braided narrative."

Thus he wrote: "The central problem of historical writing is to create

a set of structural and stylistic devices which mediates successfully

between the difficult requirements of history-as-science and history-as-art."74

Somehow, in that light, my objections to seeing history as scientific

vanished. Like scientists, historians master sophisticated empirical methods.

They collect and evaluate evidence of various sorts (published documents,

archival sources, oral interviews, photographs, etc.). Also like scientists,

historians employ various theories (from sociology, from Marxism, from

major historical syntheses, etc.) to help frame questions and formulate

hypotheses.

To stop there, however, would be to misrepresent the enterprise, because

historians—to be fully deserving of that designation—must

also shape their material according to avowedly literary aspirations.

In Fischer's words: "They deliberately seek to create a work which has

an aesthetic and an ethical and a metaphysical dimension, at the same

time that they try to remain true to the scientific requirements of their

calling."75

Especially in my fields of study, the tide of historical sociology has

not yet crested. "Sociology of Knowledge" continues to expand its influence

in both the history of technology and the history of science. Yet as I

conduct my land research and explore the terrain of Western New York,

I'm increasingly aware that within me there exists no cognitive structure

more fundamental than storytelling.

All this was very much on my mind as I began my day trip to Rose Lake.

That summer I was finally reading Joseph Campbell's The Hero with

a Thousand Faces76 cover-to-cover. It's a book I had long

dipped into, but now I was seeing things I hadn't before.

Using examples from dozens of quite different cultures, throughout the

world and across time, the book abstracted one of humankind's most important

stories. After being called to adventure, the hero (or heroine):

—encounters perils and finds assistance,

—achieves enlightenment or obtains some valuable boon,

and

—returns home to bring that advantage to his (or her) fellow

humans.

In past contact with the book, I had focused on those idealized steps.

But in my cover-to-cover reading, what struck me about the stories were

their differences, in detail after detail. On that basis, how could any

of them be considered true in a literal sense?

By taking a comparative approach, however, Campbell wasn't rejecting

mythical truth. Instead, he was demonstrating that mythical truth lies

at a different level—namely, the level of symbols.

When I reached this point in my thinking I found myself turning to a

consideration of ancient Greek science. The very first philosopher-scientists

had assumed that the changes we perceive in the natural world are real.

But in the early fifth century BC, Parmenides argued that his predecessors

had been fundamentally misled by their senses. Only reason can lead us

to Truth, he argued, and what we learn if we appeal to reason is that

Truth is one and indivisible, eternal and changeless.

I had long been skeptical of Parmenides's position, but in the context

of Campbell's book it began to make sense. Beyond the reach of our words—in

either their literal or their symbolic senses—is an Ultimate Reality

that just is what it is, and that's pretty much all that can be said about

it. But between Ultimate Reality and the literal reality we create with

our concepts (and that our concepts create for us) lies a realm where

words no longer carry literal meaning but where meaning still exists in

symbolic form.

That was the realm Campbell was showing me. The hero's journey was all

about entering the realm of symbols and then returning to his (or her)

compatriots, thus helping them renew their collective spiritual life.

Though none of the stories in Campbell's book might be true in their literal

details, all aimed at taking people as far into truth as mortals could

go without stumbling into oblivion or becoming one with God.

With all that on my mind as I left Rochester, I was largely unaware of

the terrain I was driving across. But along Route 36 in Hornell, I caught

sight of locomotives switching boxcars in a rail yard—which got

me off the road and into a nearby parking lot to watch for a while.

Resuming my trip, I turned right onto Route 248 at Canisteo and began

following Bennetts Creek to the village of Greenwood. Small in scale,

yet with houses neatly kept up, the village put me in mind of Walt Franklin's

chapbook Little Water Company77.

I had met Walt at meetings of the Bath Area Writers Group a decade or

more ago, and the basic aim of his chapbook had long appealed to me. "When

I settled in the township [of Greenwood]," he explained in the preface,

"one idea I had for poetry was to take a walking tour. . . by way of its

watershed. . . ." The result was a series of poems, each describing his

experiences with a particular stream.

Beyond Greenwood the terrain again asserted itself. Ever since Canisteo

the highway had been climbing, and when I reached the marshy terrain of

the divide, I stopped for a short walk. There wasn't much of a shoulder,

and the uneven ground made my knee ache. While hiking a streambed the

week before, I had slipped and fallen. The result was a sore knee that

wasn't fully healed.

"How much stream exploring am I going to be able to do today?" I wondered

as I resumed driving. But as my train of thought continued, I realized

that there was more on my mind than just the limitations posed by my physical

disability.

As a kind of story, the hero's journey is still very much with us, and

the night before I had watched one on videotape. In the movie Contact,78

Jodie Foster plays Dr. Ellie Arroway, an astronomer who uses radio telescopes

to seek signs of intelligent life in deep space. Not only does she succeed,

but she also becomes the lone human sent to make contact with the aliens.

Her story was definitely a hero's journey, and what ran through my mind

as I headed toward Genesee, Pennsylvania, was her cry as she beheld features

of the universe never before seen by earthlings at close range. No longer

was her scientific training of any use. Into her personal recording unit,

all she could say was: "They should have sent a poet!"

From the outset I had been uneasy about making a trip to the sources

of the Genesee. Maybe I wasn't the right person to pull it off. After

all, I wasn't a poet; I couldn't plan a series of poems about the various

streams that come together to form the river. But neither was I a scientist;

I couldn't extract samples of organic remains and radiocarbon date them.

True, as an historian I was a master of the braided narrative. But what

guarantee did I have that my trip would turn up anything worth writing

about? None; none at all. Still, I wanted to give it a shot. So, fortified

by lunch at the Sunoco deli in Genesee, I set out to test whether or not

the literal places on my list would speak to my sense of storied terrain.

Beyond Ulysses, I followed by car the primary stream of the Genesee's

East Branch, until I reached a small pond near a house. From there the

drainage depression extended up the mown backyard and into a wooded hilltop.

I suppose I could have asked for permission to explore, but my response

to the place wasn't positive enough to justify the attempt.

Driving to the Genesee's Middle Branch, I did stop at the convenience

store at Gold for a cold soft drink. Immediately upstream, the Middle

Branch split into several smaller streams, and by car I followed the one

that went to Raymond. Again, however, I felt no inclination to get out

and walk.

My starting point for the West Branch was the village of Ellisburg, where

I drove around long enough to see how the various smaller streams joined

to form the West Branch. Then I followed one of the component streams—Rose

Lake Run—along Route 244 south. Also following Rose Lake Run had

once been the New York and Pennsylvania Railroad. My atlas still marked

its route with a dotted red line, but as I drove I saw no obvious physical

traces.

For a short distance Route 244 jogged up the side of the valley, to Andrews

Settlement, Pennsylvania, and then dipped back down. When the road once

again crossed Rose Lake Run, I hoped to pick up signs of the old railbed.

Again, however, nothing—though a little further, on the right, was

a large industrial facility of some sort.

Continuing to Lewis Corner, I had one last chance to intersect the railbed.

But still no luck. Finally I headed back to the industrial facility. This

time I noticed several open doors, and here—unlike the other locations—I

felt a definite tug. "If I don't stop and try asking," I said to myself,

"I'm not gonna get anywhere."

Just inside one of the open doors sat an older man, and I explained to

him that I was down from Rochester for the afternoon, looking for the

railbed and wanting to follow it to Rose Lake. I expected his reply to

be a curt, "No, we'd rather you didn't do that." To my amazement, however,

he responded positively.

He told me about a side road to the lake; I could drive there if I wanted.

But he also said that the old railbed wasn't far from where we were talking.

When I expressed my preference for a hike, he accompanied me across the

highway to a point where I could see the railbed in the woods.

From then on, I was sure I'd have the kind of literal experience I was

seeking. Of course, I didn't know what the details would be. But with

an abandoned railbed underfoot, an ancient lake ahead, and perfect weather

for hiking, I knew that the details would take care of themselves.

Before I could start, however, I got caught up in an exciting new idea.

In his youth the man had seen steam locomotives operating on this line,

but what actually captivated me was his current workplace. It's a compressor

station for a natural gas storage field, where three different interstate

pipeline companies send their gas to be pumped into strata 5000 feet below

the surface.

The heyday of America's railroads was long gone, but at their peak the

entire country had been crisscrossed by the lines of many different companies.

Now, however, I found myself at a very different kind of junction. What

was more, the strata nearly a mile below were being managed as part of

the nation's energy system. Porous rock was being filled with gas, thus

creating a reservoir for use whenever need warranted.

After the man left, I was at first more aware of the compressor station

than the trail. I couldn't wait to get out my camera, for a shot back

across the highway:

Fortunately, from then on I had no trouble turning my attention to the

rich texture of the trail. The railbed itself was covered with grass,

ferns, and occasional fallen tree branches. To my immediate left was a

wooded hillside, and to my immediate right the land dropped down several

feet to the stream.

Where the railbed once angled across the streambed, it had been washed

out. But just before I reached that gap, I could see a beaver dam arcing

off to the right, tying the railbed where I stood to the steep hillside

on the other side of the stream. The effect was to raise the level of

the lake, making it more extensive than it otherwise would have been.

I found I was able to walk along the dam, but the far hillside was too

steep for easy hiking—especially with my bum knee. To continue I'd

have to leave the railbed and try skirting the lake's other edge.

As a shortcut to the main body of water, I walked across a thistle-choked

field—which probably couldn't be mowed because the lake's raised

level blocked access to it. For the rest of the way I followed a modest

trail that sometimes dipped down to water level and other times rose ten

to twenty feet up the hillside.

At first the lake's surface was covered by water lilies, and looking

back in the direction of the railbed, I could see the low conical structure

of the beavers' house:

Further along, however, the water deepened and became clear of plants:

The head of the lake wasn't especially marshy, and in crossing the tiny

inlet stream I noticed no flowing water. By then, however, I wasn't concentrating

on the lake but on the house whose grassy yard ran all the way down to

the water's edge. Because I felt so conspicuous, I moved quickly, keeping

close to the lake—though halfway along I did stop for a picture,

looking across the water to where I had been hiking a few minutes before:

I never completely encircled the lake. Upon reaching the foot of a gravel

road, I took it up the hill to the highway and returned to the compressor

station that way. By then the man who had helped me was gone, and seeing

no one else, I too left.

But my trip wasn't completely over. For fun, I returned via Route 19

through Belmont, where I stopped to admire the dam—a low, stepped-structure

whose curved lines were hard to capture in a single picture:

During the trip itself, I had stayed focused on my literal surroundings

and only vaguely sensed the symbolic terrain I was reaching. Not until

I was back in Rochester did I fully appreciate how important the experience

had been.

In my imagination, I now realize, there exists a pool much like Rose

Lake. Smaller in size and definitely less developed, it lies far from

human civilization. From its depths things rise unbidden—sometimes

joy-making treasures, other times, sweat-inducing fears. In either case,

what flows out of the pool are stories.

When I attempt to understand something—anything—the furthest

I can take the effort is the edge of that pool. As ideas surface, I may

work with them a while. As a result, my writing often emerges a considerable

distance downstream—in which case the words feel more like precisely

engineered concrete than beaver-woven sticks. But through all my writing

there flows at least some of the pool's waters, and whatever depth my

essays possess is a direct result of this wonderful pool.

Illustrations supplied by the author

Notes

66. Alan R. Geyer and William H. Bolles, Environmental

Geology Report No.7 (Harrisburg: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 1979),

pp. 131-132; map, p. 132.

67. Surficial Geology and Geomorphology of Potter County, Pennsylvania,

U. S. Geological Survey Professional Paper No. 288 (Washington, DC: U.

S. Government Printing Office, 1956), p. 1.

68. G. H. Crowl and W. D. Sevon, Glacial Border Deposits of Late Wisconsinan

Age in Northeastern Pennsylvania, General Geology Report No. 71,

Pennsylvania Geological Survey, 4th Series (Harrisburg, 1980), p. 4.

69. Chet Raymo and Maureen E. Ramo (Old Saybrook, CT: Pequot Press, 1989),

p. 132.

70. Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History (New

York: Norton, 1958).

71. Rosemary Sheed, trans. (London: Sheed and Ward, 1958), p. 188.

72. Eliade, p. 200.

73. Typescript essay dated 8 May 1979.

74. “The Braided Narrative: Substance and Form in Social History,”

in Angus Fletcher, ed., The Literature of Fact: Selected Papers from

the English Institute (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976),

p. 109.

75. Fischer, p. 114.

76. 2nd Ed. (Princeton University Press, 1968).

77. Fredonia, NY: White Pine Press, 1986.

78. Directed by Robert Zemeckis (Warner Brothers, 1997).

|